Why attention deserves your attention?

What is Attention?

At its core, attention is about figuring out what matters most. In machine learning models, attention helps focus on the most relevant pieces of information when making a decision.

For example, in large language models (LLMs), attention allows the model to weigh different words in a sentence based on their importance to the current word being processed—like realizing that in the sentence “The cat that chased the mouse was hungry,” the word “cat” is more important than “mouse” when deciding what “was hungry” refers to.

In large vision models (LVMs), attention helps the model understand how different parts of an image relate—for instance, connecting a person’s face and their hand to understand that someone is waving.

This mechanism gives models a kind of global awareness: instead of looking at information in isolation, they learn to prioritize and connect the most relevant parts of the input. That’s what makes attention so powerful—it lets the model decide what to focus on, dynamically, depending on the task.

But how exactly does a model know where to look? That’s where Scaled Dot-Product Attention comes in—and trust me, it’s not as scary as it sounds.

Mathematical Intuition

To reiterate, attention figures out what matters in an input sequence. But how does this magic actually work under the hood? Let’s build some mathematical intuition.

Suppose we have a sequence of word vectors—each one representing a word in the sentence. Our goal is to compute how much each word should attend to every other word. In essence, we want a score for every pair of words: “how relevant is word $j$ to word $i$?”

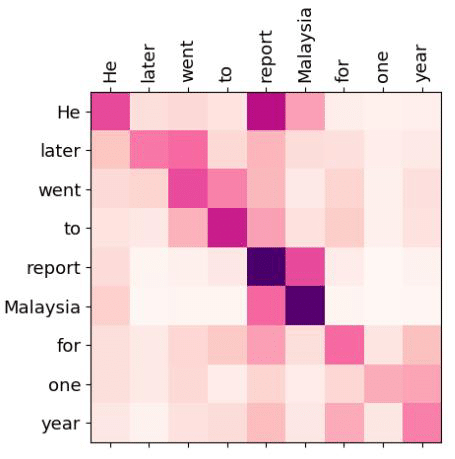

A natural way to represent this is with a matrix of probabilities. If we have a 10-word sentence, we can build a $10×10$ matrix where the entry at position $(i,j)(i, j)(i,j)$ tells us how much word $i$ should focus on word $j$.

A higher value means stronger attention—more focus. For example, in the matrix above, the word “he” attends strongly to both itself and “report”. What we understand semantically is being captured here mathematically: the model is learning these relationships through vector similarity and normalization.

Scaled Dot-Product Attention (SDPA) - Intuition

One of the common ways to compute the attention output is via SDPA. As a menacing as it sounds, it’s quite simpler once we break it down. Let’s first try to understand what Q, K and V represent.

\[SelfAttention(Q,K,V) = softmax(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}).V\]QKV values

Embeddings encode meanings, not roles

We might have the question if the goal behind attention is to see how much a word relates to the rest of the words, can we compute something like a cosine similarity matrix for the input embeddings? Answer is no since then the text embeddings are a representation of the word with any local context. By computing a cosine similarity matrix, we would end up capturing how similar the words are and not necessarily which words are important in the context of the sentence.

Input embeddings capture what a word is, not what it’s doing in context. So comparing raw embeddings directly is like asking:

“How similar are the words ‘bank’ and ‘river’?”

Useful in some sense, but it misses who’s looking and why.

Think of Q, K, V as learned projections that give each word a job in the attention mechanism. So instead of comparing raw embeddings, we project each word into these three views:

- Query space: what each word wants to find

- Key space: what each word exposes

- Value space: what each word contributes

And very imporantly, this gives us:

- Asymmetry: attention from A to B ≠ B to A (important!)

- Learnable flexibility: Q, K, V projections are trained to fit the model’s goals

- Control: the model can focus on different things depending on whether it’s encoding context, generating text, or attending across modalities

- Easy to train: attention mechanism is parallelizable and matrix-multiplicable

Attention Scores

Now for every input embedding we have projected them to get the query, key and value vectors. Next step is to compute how each token relates to the rest. A quick and easy way is to calculate the scaled dot product (\(QK^T\)). Breaking this down:

- Basically for we take \(q_0\) vector and multiply that with \(k_0, k_1, k_2, ... k_n\) where \(n\) is the number of tokens

- Similarly we repeat this process for \(q_1, q_2, ... q_n\) vectors

- The previous 2 steps basically describe a matrix multiplication of \(QK^T\)

What we end up with is called attention scores where the value at $[i,j]$ represents how much does \(i_{th}\) word care about \(j_{th}\) word. These are raw numbers and based purely on vector similarity. These values are typically unnormalized, could be big, small, or even negative.

Attention Weights

The term “weights” here is closely related to the idea of a weighted sum — where we assign different levels of importance to each value in a group. In the context of attention, we’re computing how important every other token is relative to the current one.

You can think of it as a way to “zero in” on the most relevant tokens: given a set of attention scores (which reflect raw similarity), how do we turn them into a meaningful focus?

Mathematically, we normalize these scores using the softmax function, which transforms them into a probability distribution. This is a technique borrowed from traditional classifiers, where softmax helps pick the most likely class. In attention, it lets each token decide how much to attend to every other token — effectively letting it “focus” where it matters most.

\[attention\_weights = softmax(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}})\]Attention Ouptuts

Now that we know which tokens we need pay attention to, what is the final value we pass on? This is why we multiple the attention weights with value vector $V$ and pass it on.

One might ask, why not pass just the weights or multiply it with the input embeddings and pass on? Because you don’t want just a re-weighted average of static embeddings. You want the model to learn what information to contribute during attention, separate from what it uses to decide relevance.

\[SelfAttention(Q,K,V) = softmax(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}).V\]A python implementation of the same would look something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

def compute_attention(q, k, v):

attn_scores = q @ k.T

scale = math.sqrt(query.size(-1)) # Embedding dim

attn_weight = torch.softmax(attn_weight, dim=-1)

return attn_weight @ v

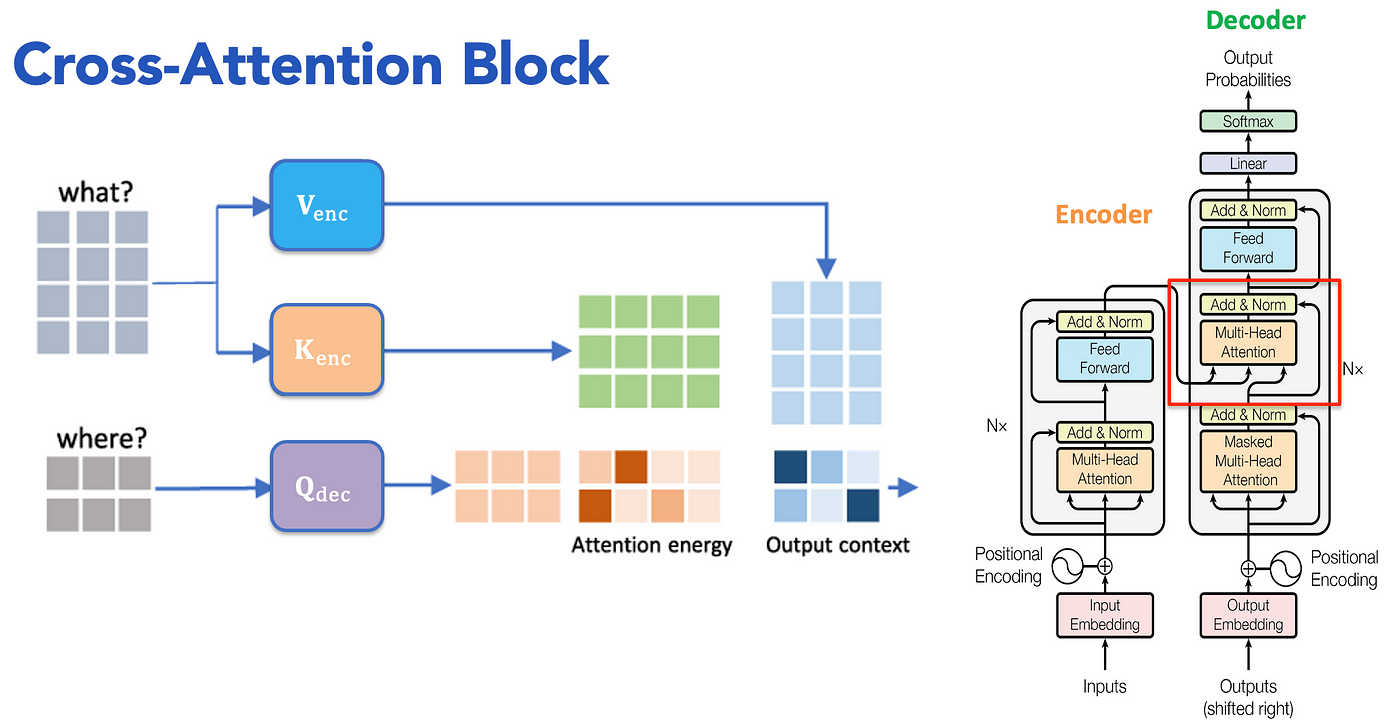

Cross Attention

So far, we’ve talked about attention within a single sequence—self-attention—where each token attends to every other token in the same input.

But what happens when you want one sequence to attend to another? That’s where cross-attention comes in. Say you want to train an LLM to translate text from English to French. Self attention allows the model to understand the context and semantics of the input sentence in a given language, whereas cross attention allows the model to understand the context and sematics across languages so it can translate better.

Mathematically, it’s largely the same with a small twist. We take the query vectors from the target langauge (decoder) and use the key & value vectors from the source language (encoder).

\[CrossAttention(Q_{dec},K_{env},V_{env})=softmax(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}).V\]Multi-Head Attention (MHA)

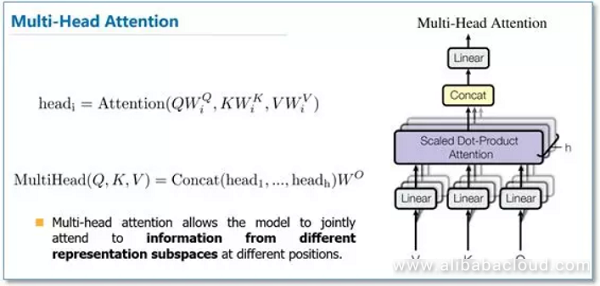

Attention is a learnable way to compute how every token relates to every other token. This works great—but as the context window grows, those relationships become increasingly complex. A single attention head (i.e., a single set of Q, K, V projections) can only capture one kind of interaction at a time.

Multi-head attention (MHA) addresses this by allowing the model to learn multiple independent attention mechanisms in parallel. Instead of producing just one set of $QKV$ vectors for each token, we generate several—one per head. Each head computes its own attention output, focusing on different aspects of the input. These outputs are then concatenated and projected again.

This means each token ends up with a richer, multi-faceted context-aware representation.

Why MHA is a big win:

- Multiple views of the same sequence: Each head can learn to focus on different types of relationships—syntax, semantics, positional dependencies, etc.

- No redesign needed: MHA is a clean extension of scaled dot-product attention. The extra heads are just an added dimension in the $$QKV$$ tensors.

- Training-friendly: Since the structure remains differentiable and parallelizable, it plays well with GPUs and gradients.

- Scales with model depth: Deeper layers + more heads = more nuanced understanding, without needing more exotic architectures.

Raw Attention Performance

Let’s try to evaluate the performance of a raw unoptimization attention computation that would look something like:

1

2

3

4

5

def compute_attention(q, k, v):

attn_scores = q @ k.T

scale = math.sqrt(query.size(-1)) # Embedding dim

attn_weight = torch.softmax(attn_weight, dim=-1)

return attn_weight @ v

Looks pretty simple and innoncent right unit you realize it can melt your GPU!

Let’s say the $QKV$ shape is $(batch_size, seqlen, nheads, headdim)$ or $(BSHD)$ for simplification.

What would the runtime and memory complexity look like as function of these variables?

- There are two matrix multiplications of note $Q.K^T$ and $attn_weights.V$

- For \(Q.K^T\), we are multiplying two matrices of size \(S * D\) and \(D * S\) over \(B * H\) so the runtime comes about \(O(BHS^2D)\)

- For the latter, we multiply \(S * S\) and \(S * D\) over \(B * H\), the runtime still remains comes to \(O(BHS^2D)\)

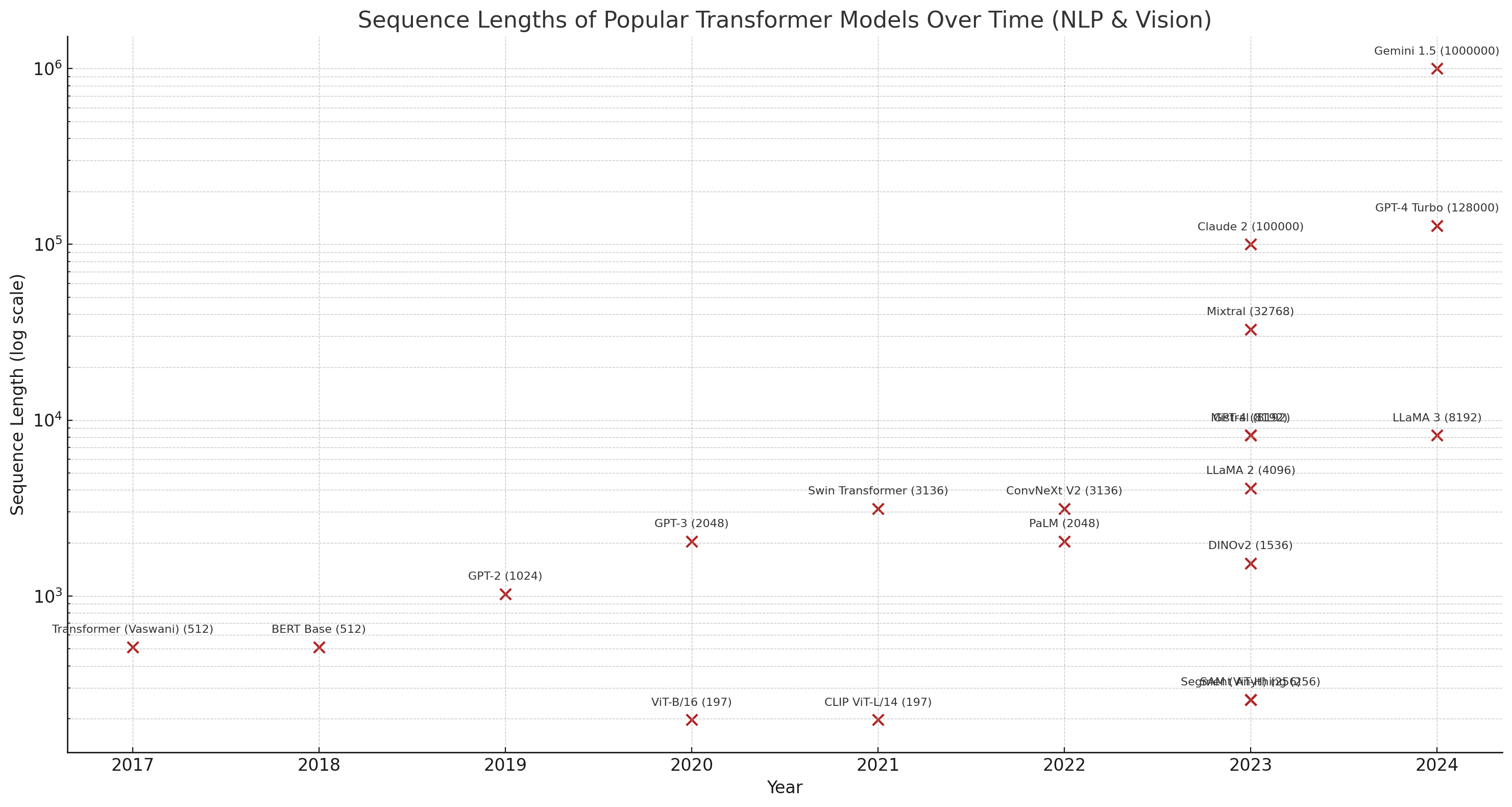

Key takeaway is that the both runtime and mrmory scales quadratically with respect to the $$sequence_length$$

If you’re thinking why is this bad and why should we be worried, I’ll try to explain why. Let’s compute the GPU requirement for a few examples:

- Say \(shape(Q,K,V) = (1, 4000, 32, 128)\) and \(datatype\) is bfloat16 which means each value takes 16 bits so 2 bytes

- Each \(QKV\) tensor would take up about \(4000 * 32 * 128 bytes\) ~ \(31.25 MB\)

- And the attention scores of shape \((1, 32, 4000, 4000)\) would take up ~ \(976.56 MB\)

You might look at that and pfft say that doesn’t look much. But take a looks at this:

llama3-8Bhad attention score of shape \((1, 32, 8096, 8096)\) which needs ~ \(3.9 GB\)llama3-70Bhad attention score of shape \((1, 64, 8096, 8096)\) which needs ~ \(7.82 GB\)- For large vision and video models, this number can go easily up to \(16,000\) which needs ~ \(159.47GB\)

And keep in mind, these numbers are on top of the memory required for model weights and activations!

Moreover, with time this numbers seems to be going higher and higher.

From companies like OpenAI, Meta, Adobe, Google:

- In large-scale inference pipelines, attention kernels are:

- Among the most frequently called CUDA kernels

- The first to be fused or rewritten in Triton/CUDA

- At high batch sizes, MLPs catch up a bit—but attention still dominates for autoregressive generation.

- Short sequence (<512) → attention is comparable to or slightly less than MLP.

- Long sequence (2048+) → attention is often the bottleneck.

- Extreme sequence (8K–128K) → attention cost explodes quadratically, dominating all other layers.

To summarize:

- Sequence lengths have a quadratic relation to both memory and latency

- Sequence lengths are increasing to produce better quality models which leads to higher GPU requirement

- More GPUs and larger GPUs mean more dollars given GPUs are limited and expensive

Why Attention Matters

Attention isn’t just a clever trick for computing relevance—it’s the beating heart of modern deep learning models. By letting models dynamically decide what to focus on, attention unlocks a level of flexibility and expressiveness that static architectures struggle to match.

But here’s the catch: all this power comes at a cost.

If we want attention to scale to longer documents, higher-res images, or massive multimodal inputs, we need to get smarter about how we compute it.

That’s where optimization comes in. Things like sparse attention, low-rank approximations, fused kernels, and memory-efficient softmax aren’t just nice-to-haves—they’re the reason models like GPT-4 and Gemini don’t melt your GPU and your pockets!!!

In future posts, we’ll peel back the curtain on the mechanics and tricks behind optimizing attention, starting with the inner loop of it all: Scaled Dot-Product Attention (SDPA). We’ll break it down simply, show how it’s implemented efficiently, and explore how different libraries and hardware backends optimize it under the hood.

Stay tuned, we’re just getting warmed up. Brrr..