LLMs Explained - Part 1 - Tokenizers

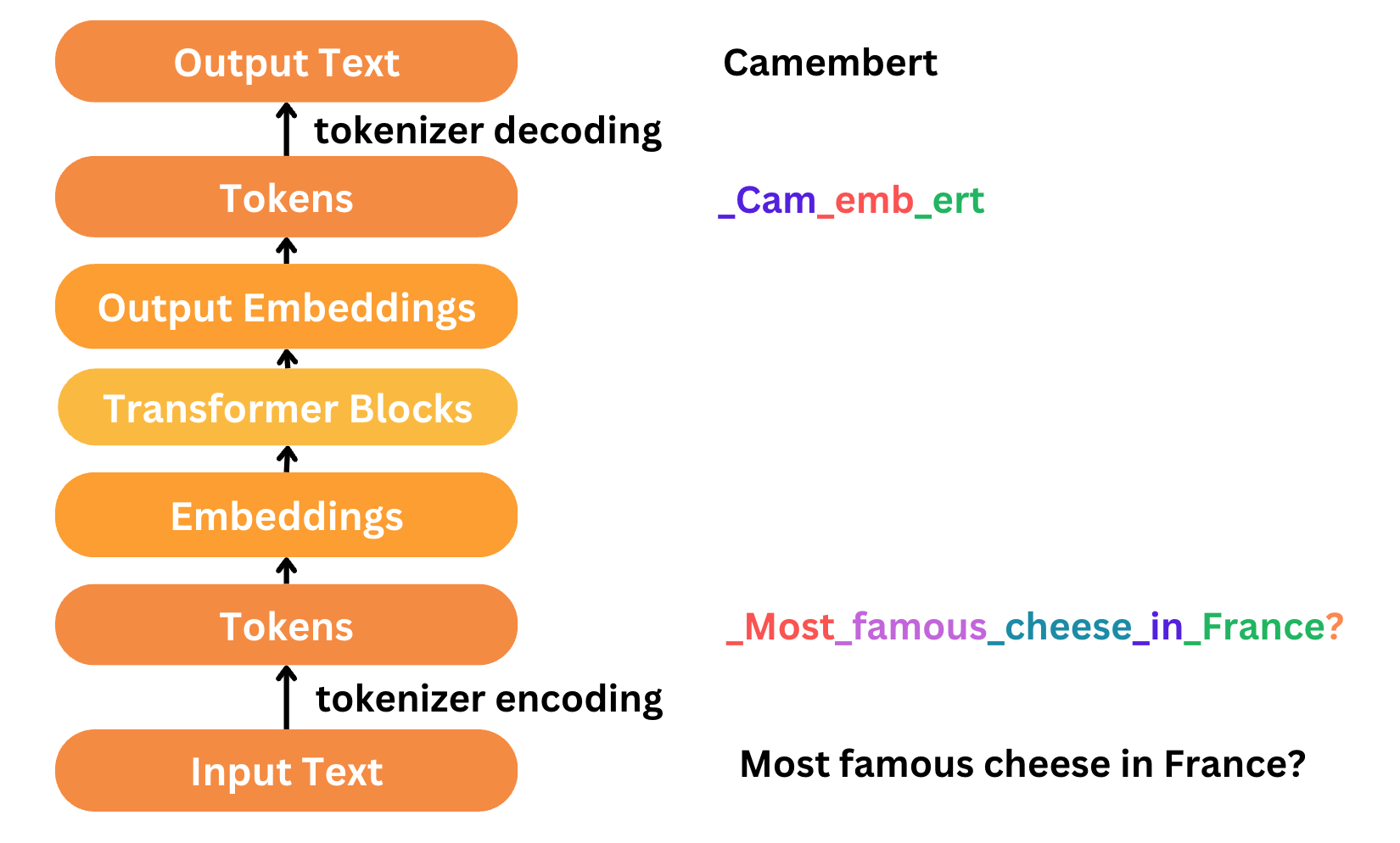

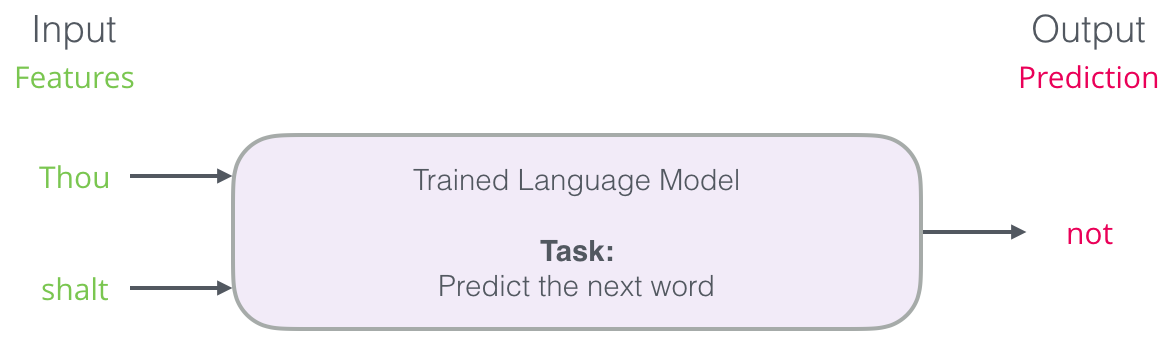

Language Model

One of the most popular and early applications of NLP was next word prediction. All of us have probably leveraged this capability from our smartphone’s keyboard! Next-word prediction is a task that can be addressed by a language model. A language model can take a list of words (let’s say two words), and attempt to predict the word that follows them.

We can expect a language model to do something as follows

The best part about language models is that there is plenty of textual data to go around. But how do we convert it to a format that the ML model can understand? This is where tokenization comes it, which serves as an essential pre-processing step to take the raw input data and convert it to a format which the ML model can train on.

Tokenization

Tokenization is a preprocessing step that involves breaking down text into individual units (tokens), such as words, phrases, or subwords, which can then be used as input for various NLP models, including Word2Vec.

For instance, the sentence “The cat sat on the mat” would be tokenized into the individual words [“The”, “cat”, “sat”, “on”, “the”, “mat”].

Tokenization is the first step and the last step of text processing and modeling. Texts need to be represented as numbers in our models so that our model can understand.

Moreover there is a lot of weird behaviour in LLMs that can often we traced back to tokenization.

- Why can’t LLM spell words? Tokenization.

- Why can’t LLM do super simple string processing tasks like reversing a string? Tokenization.

- Why is LLM worse at non-English languages (e.g. Japanese)? Tokenization.

- Why is LLM bad at simple arithmetic? Tokenization.

- Why did GPT-2 have more than necessary trouble coding in Python? Tokenization.

- Why did my LLM abruptly halt when it sees the string “<endoftext>”? Tokenization.

- What is this weird warning I get about a “trailing whitespace”? Tokenization.

- Why the LLM break if I ask it about “SolidGoldMagikarp”? Tokenization.

- Why should I prefer to use YAML over JSON with LLMs? Tokenization.

- Why is LLM not actually end-to-end language modeling? Tokenization.

Early Tokenization Techniques

Word-based Tokenization

The first type of tokenizer that comes to mind is word-based. It’s generally very easy to set up and use with only a few rules, and it often yields decent results. The simplest form of word tokenization is using whitespace tokenization where tokens are separated by whitespace characters (spaces, tabs, newlines).

There are also variations of word tokenizers that have extra rules for punctuation. With this kind of tokenizer, we can end up with some pretty large “vocabularies,” where a vocabulary is defined by the total number of independent tokens that we have in our corpus.

Each word gets assigned an ID, starting from 0 and going up to the size of the vocabulary. The model uses these IDs to identify each word.

If we want to completely cover a language with a word-based tokenizer, we’ll need to have an identifier for each word in the language, which will generate a huge amount of tokens. For example, there are over 500,000 words in the English language, so to build a map from each word to an input ID we’d need to keep track of that many IDs.

Furthermore, words like “dog” are represented differently from words like “dogs”, and the model will initially have no way of knowing that “dog” and “dogs” are similar: it will identify the two words as unrelated. The same applies to other similar words, like “run” and “running”, which the model will not see as being similar initially.

Finally, we need a custom token to represent words that are not in our vocabulary. This is known as the “unknown” token, often represented as ”[UNK]” or ”<unk>”. It’s generally a bad sign if you see that the tokenizer is producing a lot of these tokens, as it wasn’t able to retrieve a sensible representation of a word and you’re losing information along the way.

One way to reduce the amount of unknown tokens is to go one level deeper, using a character-based tokenizer.

Character Tokenization

Character-based tokenizers split the text into characters, rather than words. This has two primary benefits:

- The vocabulary is much smaller.

- There are much fewer out-of-vocabulary (unknown) tokens, since every word can be built from characters.

This approach isn’t perfect either. Since the representation is now based on characters rather than words, one could argue that, intuitively, it’s less meaningful: each character doesn’t mean a lot on its own, whereas that is the case with words. However, this again differs according to the language; in Chinese, for example, each character carries more information than a character in a Latin language.

Another thing to consider is that we’ll end up with a very large amount of tokens to be processed by our model: whereas a word would only be a single token with a word-based tokenizer, it can easily turn into 10 or more tokens when converted into characters.

Tokenization with libraries

nltk

Tokenizers divide strings into lists of substrings. For example, tokenizers can be used to find the words and punctuation in a string:

1

2

3

4

5

6

>>> from nltk.tokenize import word_tokenize

>>> s = '''Good muffins cost $3.88\nin New York. Please buy me

... two of them.\n\nThanks.'''

>>> word_tokenize(s)

['Good', 'muffins', 'cost', '$', '3.88', 'in', 'New', 'York', '.',

'Please', 'buy', 'me', 'two', 'of', 'them', '.', 'Thanks', '.']

This particular tokenizer requires the Punkt sentence tokenization models to be installed. NLTK also provides a simpler, regular-expression based tokenizer, which splits text on whitespace and punctuation:

1

2

3

4

>>> from nltk.tokenize import wordpunct_tokenize

>>> wordpunct_tokenize(s)

['Good', 'muffins', 'cost', '$', '3', '.', '88', 'in', 'New', 'York', '.',

'Please', 'buy', 'me', 'two', 'of', 'them', '.', 'Thanks', '.']

We can also operate at the level of sentences, using the sentence tokenizer directly as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

>>> from nltk.tokenize import sent_tokenize, word_tokenize

>>> sent_tokenize(s)

['Good muffins cost $3.88\nin New York.', 'Please buy me\ntwo of them.', 'Thanks.']

>>> [word_tokenize(t) for t in sent_tokenize(s)]

[['Good', 'muffins', 'cost', '$', '3.88', 'in', 'New', 'York', '.'],

['Please', 'buy', 'me', 'two', 'of', 'them', '.'], ['Thanks', '.']]

Caution: when tokenizing a Unicode string, make sure you are not using an encoded version of the string (it may be necessary to decode it first, e.g. with

s.decode("utf8").

NLTK tokenizers can produce token-spans, represented as tuples of integers having the same semantics as string slices, to support efficient comparison of tokenizers. (These methods are implemented as generators.)

1

2

3

4

>>> from nltk.tokenize import WhitespaceTokenizer

>>> list(WhitespaceTokenizer().span_tokenize(s))

[(0, 4), (5, 12), (13, 17), (18, 23), (24, 26), (27, 30), (31, 36), (38, 44),

(45, 48), (49, 51), (52, 55), (56, 58), (59, 64), (66, 73)]

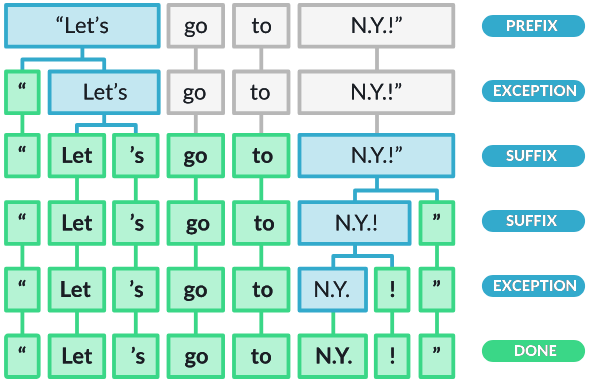

SpaCy

Note: spaCy’s tokenization is non-destructive, which means that you’ll always be able to reconstruct the original input from the tokenized output. Whitespace information is preserved in the tokens and no information is added or removed during tokenization. This is kind of a core principle of spaCy’s

Docobject:doc.text == input_textshould always hold true.

During processing, spaCy first tokenizes the text, i.e. segments it into words, punctuation and so on. This is done by applying rules specific to each language. For example, punctuation at the end of a sentence should be split off – whereas “U.K.” should remain one token. Each Doc consists of individual tokens, and we can iterate over them:

1

2

3

4

5

6

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("Apple is looking at buying U.K. startup for $1 billion")

for token in doc:

print(token.text)

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | is | looking | at | buying | U.K. | startup | for | $ | 1 | billion |

First, the raw text is split on whitespace characters, similar to text.split(' '). Then, the tokenizer processes the text from left to right. On each substring, it performs two checks:

- Does the substring match a tokenizer exception rule?

- Can a prefix, suffix or infix be split off?

We can also add special case tokenization rules using SpaCy as shown in the code below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

import spacy

from spacy.symbols import ORTH

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("gimme that") # phrase to tokenize

print([w.text for w in doc]) # ['gimme', 'that']

# Add special case rule

special_case = [{ORTH: "gim"}, {ORTH: "me"}]

nlp.tokenizer.add_special_case("gimme", special_case)

# Check new tokenization

print([w.text for w in nlp("gimme that")]) # ['gim', 'me', 'that']

gensim

We can use the gensim.utils class to import the tokenize method for performing word tokenization.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

from gensim.utils import tokenize

text = """

Founded in 2002, SpaceX’s mission is to enable humans to become a spacefaring civilization and a multi-planet

species by building a self-sustaining city on Mars. In 2008, SpaceX’s Falcon 1 became the first privately developed

liquid-fuel launch vehicle to orbit the Earth."""

list(tokenize(text))

Output : ['Founded', 'in', 'SpaceX', 's', 'mission', 'is', 'to', 'enable', 'humans', 'to',

'become', 'a', 'spacefaring', 'civilization', 'and', 'a', 'multi', 'planet',

'species', 'by', 'building', 'a', 'self', 'sustaining', 'city', 'on', 'Mars',

'In', 'SpaceX', 's', 'Falcon', 'became', 'the', 'first', 'privately',

'developed', 'liquid', 'fuel', 'launch', 'vehicle', 'to', 'orbit', 'the',

'Earth']

To perform sentence tokenization, we use the split_sentences method from the gensim.summerization.texttcleaner class:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

from gensim.summarization.textcleaner import split_sentences

text = """

Founded in 2002, SpaceX’s mission is to enable humans to become a spacefaring civilization and a multi-planet

species by building a self-sustaining city on Mars. In 2008, SpaceX’s Falcon 1 became the first privately developed

liquid-fuel launch vehicle to orbit the Earth.

"""

result = split_sentences(text)

result

Output : ['Founded in 2002, SpaceX’s mission is to enable humans to become a spacefaring

civilization and a multi-planet ',

'species by building a self-sustaining city on Mars.',

'In 2008, SpaceX’s Falcon 1 became the first privately developed ',

'liquid-fuel launch vehicle to orbit the Earth.']

You might have noticed that gensim is quite strict with punctuation. It splits whenever a punctuation is encountered. In sentence splitting as well, gensim tokenized the text on encountering \n while other libraries ignored it.

Subword Tokenization

Subword tokenization algorithms rely on the principle that frequently used words should not be split into smaller subwords, but rare words should be decomposed into meaningful subwords.

Here is an example showing how a subword tokenization algorithm would tokenize the sequence “Let’s do tokenization!“:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Let’s | do | token | ization | ! |

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) Tokenization - GPT2

BPE relies on a pre-tokenizer that splits the training data into words. Pretokenization can be as simple as whitespace tokenization like in the case of GPT-2, RoBERTa but you can also use rule-based tokenization like in XLM, FlauBERT

- After pre-tokenization, a set of unique words has been created and the frequency with which each word occurred in the training data has been determined.

- Next, BPE creates a base vocabulary consisting of all symbols that occur in the set of unique words and learns merge rules to form a new symbol from two symbols of the base vocabulary.

- It does so until the vocabulary has attained the desired vocabulary size. Note that the desired vocabulary size is a hyperparameter to define before training the tokenizer.

As an example, let’s assume that after pre-tokenization, the following set of words including their frequency has been determined:

1

("hug", 10), ("pug", 5), ("pun", 12), ("bun", 4), ("hugs", 5)

Consequently, the base vocabulary is ["b", "g", "h", "n", "p", "s", "u"]. Splitting all words into symbols of the base vocabulary, we obtain:

1

("h" "u" "g", 10), ("p" "u" "g", 5), ("p" "u" "n", 12), ("b" "u" "n", 4), ("h" "u" "g" "s", 5)

BPE then counts the frequency of each possible symbol pair and picks the symbol pair that occurs most frequently. In the example above "h" followed by "u" is present 10 + 5 = 15 times (10 times in the 10 occurrences of "hug", 5 times in the 5 occurrences of "hugs"). However, the most frequent symbol pair is "u" followed by "g", occurring 10 + 5 + 5 = 20 times in total. Thus, the first merge rule the tokenizer learns is to group all "u" symbols followed by a "g" symbol together. Next, "ug" is added to the vocabulary. The set of words then becomes

1

("h" "ug", 10), ("p" "ug", 5), ("p" "u" "n", 12), ("b" "u" "n", 4), ("h" "ug" "s", 5)

BPE then identifies the next most common symbol pair. It’s "u" followed by "n", which occurs 16 times. "u", "n" is merged to "un" and added to the vocabulary. The next most frequent symbol pair is "h" followed by "ug", occurring 15 times. Again the pair is merged and "hug" can be added to the vocabulary. The set of words now becomes:

1

("hug", 10), ("p" "ug", 5), ("p" "un", 12), ("b" "un", 4), ("hug" "s", 5)

Assuming, that the Byte-Pair Encoding training would stop at this point, the learned merge rules would then be applied to new words (as long as those new words do not include symbols that were not in the base vocabulary). For instance, the word "bug" would be tokenized to ["b", "ug"] but "mug" would be tokenized as ["<unk>", "ug"] since the symbol "m" is not in the base vocabulary. In general, single letters such as "m" are not replaced by the "<unk>" symbol because the training data usually includes at least one occurrence of each letter, but it is likely to happen for very special characters like emojis.

As mentioned earlier, the vocabulary size, i.e. the base vocabulary size + the number of merges, is a hyperparameter to choose. For instance GPT has a vocabulary size of 40,478 since they have 478 base characters and chose to stop training after 40,000 merges.

Byte-level BPE

A base vocabulary that includes all possible base characters can be quite large if e.g. all unicode characters are considered as base characters. To have a better base vocabulary, GPT-2 uses bytes as the base vocabulary, which is a clever trick to force the base vocabulary to be of size 256 while ensuring that every base character is included in the vocabulary.

With some additional rules to deal with punctuation, the GPT2’s tokenizer can tokenize every text without the need for the <unk> symbol. GPT-2 has a vocabulary size of 50,257, which corresponds to the 256 bytes base tokens, a special end-of-text token and the symbols learned with 50,000 merges.

In this context, a byte is an 8-bit unit of data that can represent a character in a given encoding (such as UTF-8). This means that the tokenization operates at the byte level, which is encoding-agnostic and can handle any character from any language or special characters uniformly.

ByteLevel BPE Tokenizer can be used in practice using HuggingFace lib as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

from tokenizers import ByteLevelBPETokenizer

# Initialize a ByteLevelBPETokenizer

tokenizer = ByteLevelBPETokenizer()

# Train the tokenizer on a corpus

tokenizer.train(files=["path/to/your/corpus.txt"], vocab_size=10000, min_frequency=2)

# Encode a text

encoded = tokenizer.encode("The cat sat on the mat.")

print("Tokens:", encoded.tokens)

print("IDs:", encoded.ids)

WordPiece Tokenization

WordPiece tokenization was originally developed for the Google Neural Machine Translation system and is widely used in models like BERT. Like BPE, WordPiece aims to handle rare and out-of-vocabulary words by breaking them into smaller, more frequent subword units. However, the algorithm for merging pairs differs slightly from BPE.

- Frequency-Based Merging

- Both BPE and WordPiece start with a base vocabulary of characters (or bytes) and iteratively merge the most frequent pairs.

- Vocabulary Size

- WordPiece aims to build a vocabulary of a fixed size, typically determined beforehand.

- Merging Criteria

- While BPE merges the most frequent pairs of symbols, WordPiece selects pairs based on a likelihood criterion that maximizes the likelihood of the training data given the current vocabulary.

- This is equivalent to finding the symbol pair, whose probability divided by the probabilities of its first symbol followed by its second symbol is the greatest among all symbol pairs

- This also leads to more semantically meaningful subwords

- While BPE merges the most frequent pairs of symbols, WordPiece selects pairs based on a likelihood criterion that maximizes the likelihood of the training data given the current vocabulary.

WordPiece Tokenizer can be used in practice as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

from transformers import BertTokenizer

# Initialize a BertTokenizer

tokenizer = BertTokenizer.from_pretrained('bert-base-uncased')

# Tokenize a text

text = "The cat sat on the mat."

encoded = tokenizer.encode_plus(text, add_special_tokens=True)

print("Tokens:", tokenizer.convert_ids_to_tokens(encoded['input_ids']))

print("Token IDs:", encoded['input_ids'])

Unigram Language Model

Unigram tokenization is based on a probabilistic model where each token is considered independently, and the goal is to find a vocabulary that maximizes the likelihood of the training data given this vocabulary. Unlike BPE and WordPiece, Unigram tokenization does not iteratively merge pairs of characters or subwords. Instead, it starts with a large initial vocabulary and gradually reduces it by removing tokens that contribute the least to the model’s likelihood.

- Initial Vocabulary: Start with a large set of subword units, often including all possible substrings of the training data.

- Likelihood Calculation: Calculate the likelihood of the training data given the current vocabulary.

- Pruning: Remove tokens that contribute the least to the likelihood, reducing the vocabulary size iteratively.

- Final Vocabulary: The process continues until the vocabulary reaches a predefined size.

Step-by-Step Process

Initial Vocabulary Start with a large set of subword units, including all characters and all possible substrings. For simplicity, let’s start with a smaller subset:

1

Vocabulary: ['p', 'l', 'a', 'y', 'i', 'n', 'g', 'e', 'r', 'd', 'play', 'ing', 'player', 'played', 'playing', 'pla', 'er', 'ed', '</w>']

Likelihood Calculation Calculate the likelihood of the training data given the current vocabulary. This involves tokenizing each word in the corpus using the current vocabulary and calculating the probability of each tokenized sequence.

Pruning Remove tokens that contribute the least to the overall likelihood. For simplicity, let’s assume we prune tokens that appear less frequently or are less useful.

Iteration Repeat the process of recalculating likelihood and pruning the least useful tokens until the vocabulary reaches a predefined size.

Unigram tokenization aims to find the optimal set of subword units that maximizes the likelihood of the training data. By starting with a comprehensive vocabulary and pruning it iteratively, it ensures that the most useful subword units are retained. This approach can capture both frequent and semantically meaningful subwords.

Unigram tokenizer can be used in practice as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

import sentencepiece as spm

# Train the SentencePiece model

spm.SentencePieceTrainer.Train('--input=path/to/your/corpus.txt --model_prefix=unigram --vocab_size=1000 --model_type=unigram')

# Load the trained model

sp = spm.SentencePieceProcessor()

sp.load('unigram.model')

# Tokenize a text

text = "The cat sat on the mat."

tokens = sp.encode_as_pieces(text)

print("Tokens:", tokens)

SentencePiece Tokenization

Subword-based tokenizers first split the text by word segments, and the whitespace information is neglected during this process. For example, the sequence of tokens [“New”, “York”, “.”] might be produced from either “New York.”, “NewYork.”, or even “New York .”.

SentencePiece is a tokenization method developed by Google that can handle a wide variety of languages and text types. It builds upon the concepts of subword tokenization and offers a robust framework for handling both character and subword tokenization. SentencePiece can use either BPE or Unigram as its subword tokenization algorithm.

The algorithm propose simple language-agnostic lossless tokenization by simply treating the input text as a sequence of Unicode characters, including whitespace, and using a consistent encoding and decoding scheme that preserves all the information needed to reproduce the original text. So it treats the input text as a sequence of characters (or bytes) without relying on spaces as delimiters. This means it can handle languages without clear word boundaries, such as Chinese or Japanese, more effectively.

- Language-Agnostic: Can handle any language, including those with no spaces between words.

- No Pre-tokenization: Does not require a pre-tokenization step to split the text into words.

- Subword Units: Supports subword tokenization using BPE or Unigram algorithms.

It employs speed-up techniques for both training and segmentation, allowing it to work with large amounts of raw data without pre-tokenization.

- For BPE segmentation, it adopts an O(N log(N)) algorithm where the merged symbols are managed by a binary heap (priority queue)

- For unigram language model, training and segmentation complexities are linear to the size of input data.

Previously text tokenization results were precomputed in an offline manner. On-the-fly processing means that it can tokenize and detokenize text dynamically during the training or inference of a Neural Machine Translation (NMT) model. SentencePiece provides C++, Python, and TensorFlow library APIs for on-the-fly processing!

SentencePiece tokenizer can be used in practice as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

import sentencepiece as spm

# Train the SentencePiece model

spm.SentencePieceTrainer.Train('--input=path/to/your/corpus.txt --model_prefix=sentencepiece --vocab_size=1000 --model_type=unigram')

# Load the trained model

sp = spm.SentencePieceProcessor()

sp.load('sentencepiece.model')

# Tokenize a text

text = "The cat sat on the mat."

tokens = sp.encode_as_pieces(text)

print("Tokens:", tokens)

Summary

- Whitespace and Rule-Based Tokenization: Simple and fast, but limited in handling complex language constructs.

- Library-Based Tokenization: More sophisticated and language-aware, yet can still struggle with edge cases.

- Subword Tokenization (BPE, WordPiece, SentencePiece): Handles out-of-vocabulary words and morphological variations well, and is essential for modern NLP models.

- SentencePiece and Unigram Language Model: Highly effective for multilingual and cross-lingual tasks, providing flexibility and robustness in tokenization.

Each tokenization technique has its own strengths and is suitable for different types of NLP tasks. Modern subword techniques like BPE, WordPiece, and SentencePiece are particularly important for training and deploying state-of-the-art language models like BERT, GPT, and their variants.

Further Readings

- https://docs.mistral.ai/guides/tokenization/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zduSFxRajkE&ab_channel=AndrejKarpathy

- https://spacy.io/usage/linguistic-features#tokenization

- https://tedboy.github.io/nlps/generated/generated/gensim.utils.tokenize.html

- https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2019/07/how-get-started-nlp-6-unique-ways-perform-tokenization/

- https://huggingface.co/learn/nlp-course/chapter2/4?fw=pt

- https://github.com/google/sentencepiece

- https://medium.com/codex/sentencepiece-a-simple-and-language-independent-subword-tokenizer-and-detokenizer-for-neural-text-ffda431e704e

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zduSFxRajkE&ab_channel=AndrejKarpathy

- https://platform.openai.com/tokenizer

- ChatGPT