What happens when you open a website?

Overview

Ever wondered what happens when you type “www.google.com” in your browser? This article aims to delve deeper in what happens right from the browser, to the network layer and right down to the physical layer.

DNS Lookup

When we enter a URL into the browser’s address bar, the browser has no idea what it means. The browser’s not equipped with the tools to figure out where to look for the address given by the user. Hence it takes the help of someone who is an expert at it - the DNS Server.

DNS Server is a phonebook of the internet

When users type domain names such as ‘google.com’ or ‘nytimes.com’ into web browsers, DNS is responsible for finding the correct IP address for those sites. Browsers then use those addresses to communicate with origin servers or CDN edge servers to access website information.

Finding the DNS Resolver

First and foremost the browser makes a DNS query to figure out what is the IP address of the url entered by the user.

Now the browser must know two things to make this call:

- What is the DNS resolver server IP address?

- How should I send?

Identifying IP address

Browser has two ways for selecting a DNS server IP:

- Use the OS level DNS which is configured from the DHCP server when the device was connected to the internet

- Use a custom DNS server like Cloudfare or Google DNS

Communication Protocol

DNS primarily uses the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) on port number 53 to serve requests. DNS queries consist of a single UDP request from the client followed by a single UDP reply from the server.

When the length of the answer exceeds 512 bytes and both client and server support EDNS, larger UDP packets are used. Otherwise, the query is sent again using the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). TCP is also used for tasks such as zone transfers. Some resolver implementations use TCP for all queries.

Browser makes a DNS query

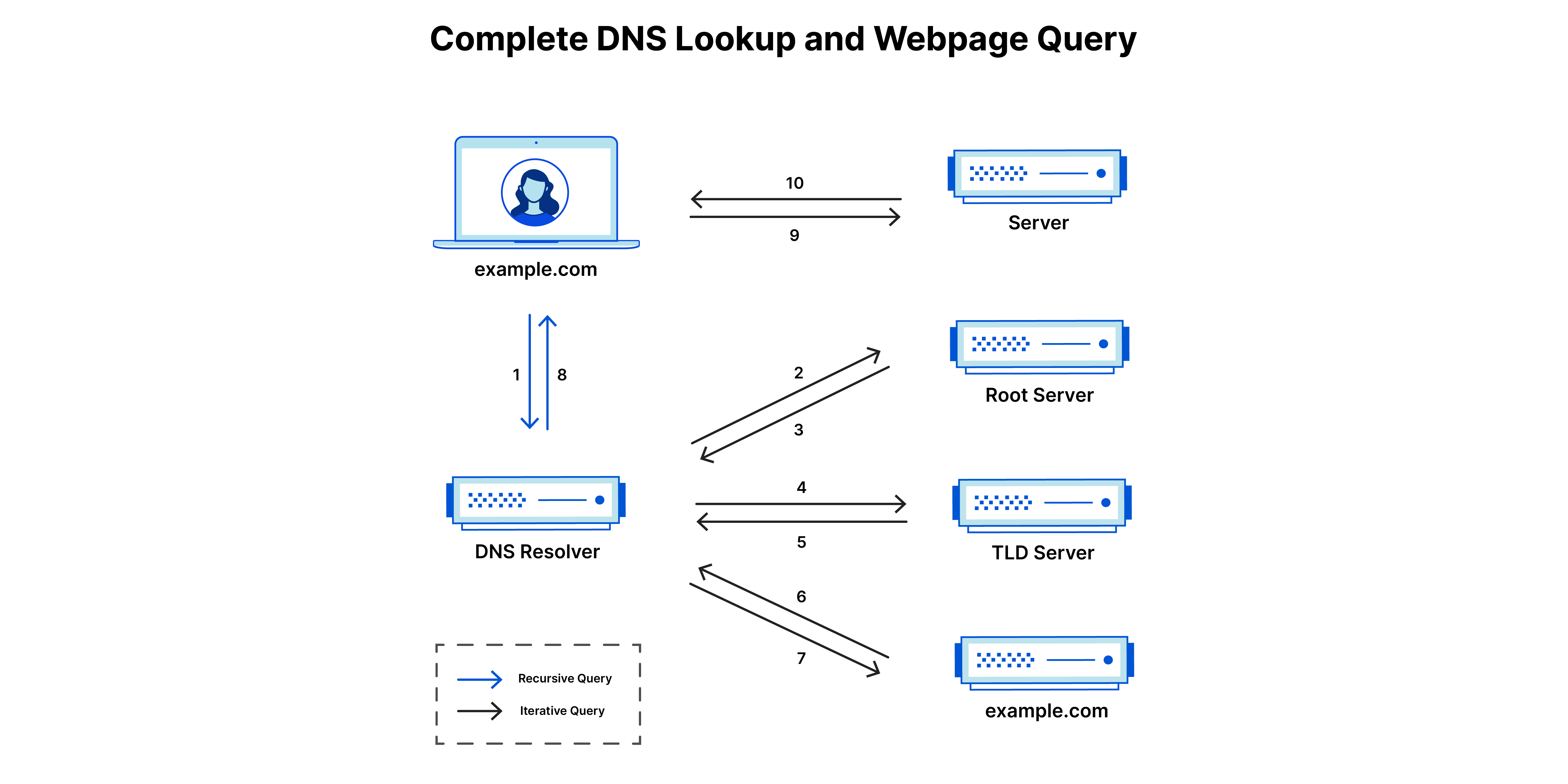

In a typical DNS lookup three types of queries occur. By using a combination of these queries, an optimized process for DNS resolution can result in a reduction of distance traveled.

- Recursive query - In a recursive query, a DNS client requires that a DNS server (typically a DNS recursive resolver) will respond to the client with either the requested resource record or an error message if the resolver can’t find the record.

- Iterative query - in this situation the DNS client will allow a DNS server to return the best answer it can. If the queried DNS server does not have a match for the query name, it will return a referral to a DNS server authoritative for a lower level of the domain namespace. The DNS client will then make a query to the referral address. This process continues with additional DNS servers down the query chain until either an error or timeout occurs.

- Non-recursive query - typically this will occur when a DNS resolver client queries a DNS server for a record that it has access to either because it’s authoritative for the record or the record exists inside of its cache. Typically, a DNS server will cache DNS records to prevent additional bandwidth consumption and load on upstream servers.

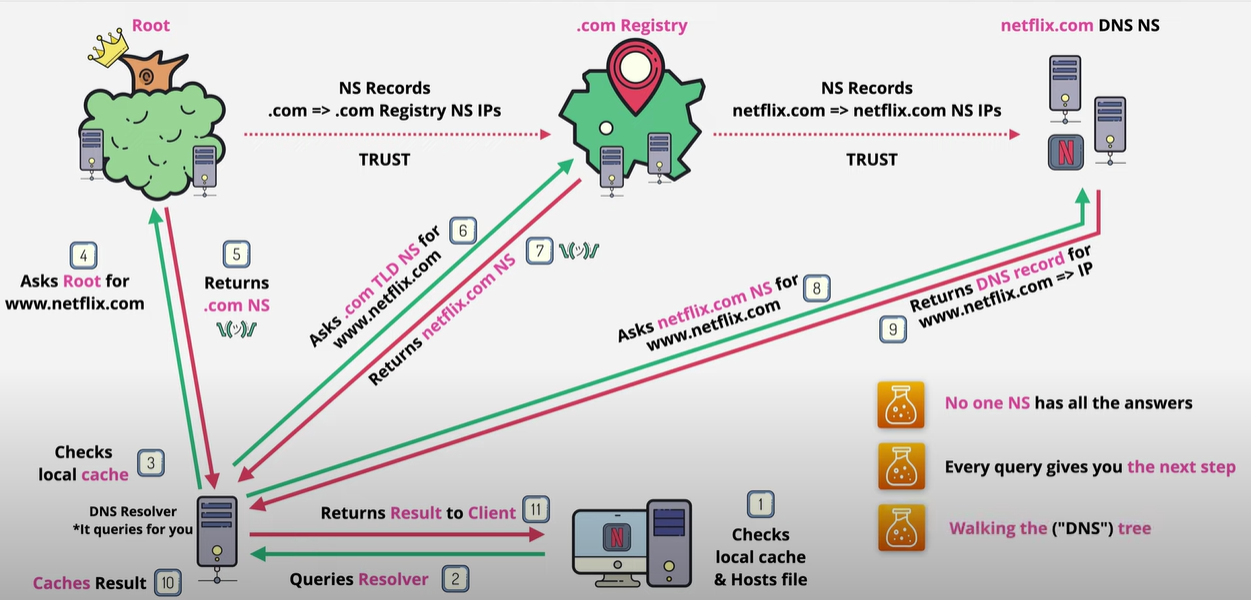

Local DNS Caching

Before the DNS query leaves the client, it checks the cache if the resolution is already available and not add to the load of the upstream servers.

There are two levels of cache checks that happen before a DNS query to the resolver is fired:

- Browser DNS caching - Modern web browsers are designed by default to cache DNS records for a set amount of time

- OS level DNS caching - When a stub resolver gets a request from an application, it first checks its own cache to see if it has the record. If it does not, it then sends a DNS query (with a recursive flag set), outside the local network to a DNS recursive resolver inside the Internet service provider (ISP).

Recursive DNS Resolver

The recursive DNS resolver it at the beginning of the DNS query and gets the request from the browser. The goal of the DNS resolver is to figure out the DNS record against the URL from the browser.

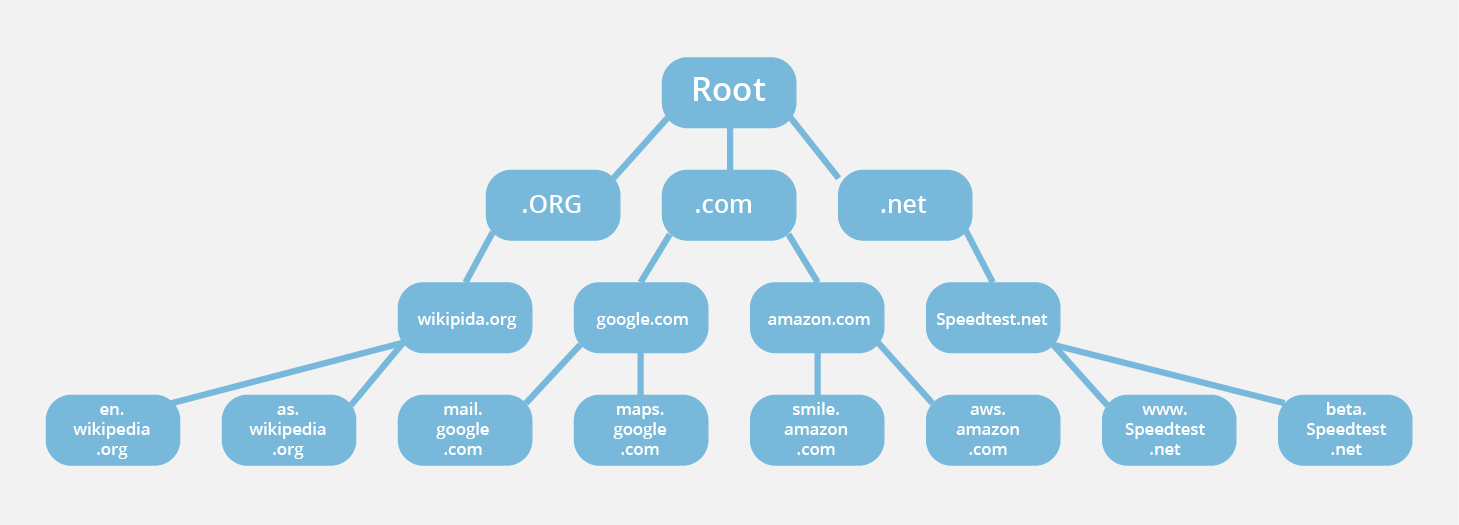

DNS root nameserver

Since the DNS root zone is at the top of the DNS hierarchy, recursive resolvers cannot be directed to them in a DNS lookup. Because of this, every DNS resolver has a list of the 13 IP root server addresses built into its software. Whenever a DNS lookup is initiated, the recursor’s first communication is with one of those 13 IP addresses.

A root server accepts a recursive resolver’s query which includes a domain name, and the root nameserver responds by directing the recursive resolver to a TLD nameserver, based on the extension of that domain (.com, .net, .org, etc.).

DNS TLD nameserver

A TLD nameserver maintains information for all the domain names that share a common domain extension, such as .com, .net, or whatever comes after the last dot in a URL.

If a user was searching for google.com, after receiving a response from a root nameserver, the recursive resolver would then send a query to a .com TLD nameserver, which would respond by pointing to the authoritative nameserver for that domain.

DNS authoritative nameserver

The authoritative nameserver is usually the resolver’s last step in the journey for an IP address. The authoritative nameserver contains information specific to the domain name it serves (e.g. google.com) and it can provide a recursive resolver with the IP address of that server.

At times, the TLD might have multiple authoritative nameservers to point to for the domain passed from the browser. This is largely to add a bit of resiliency & fault tolerance, so any of them can help with resolving the domain.

DNS Lookup - Full Journey

TCP Handshake

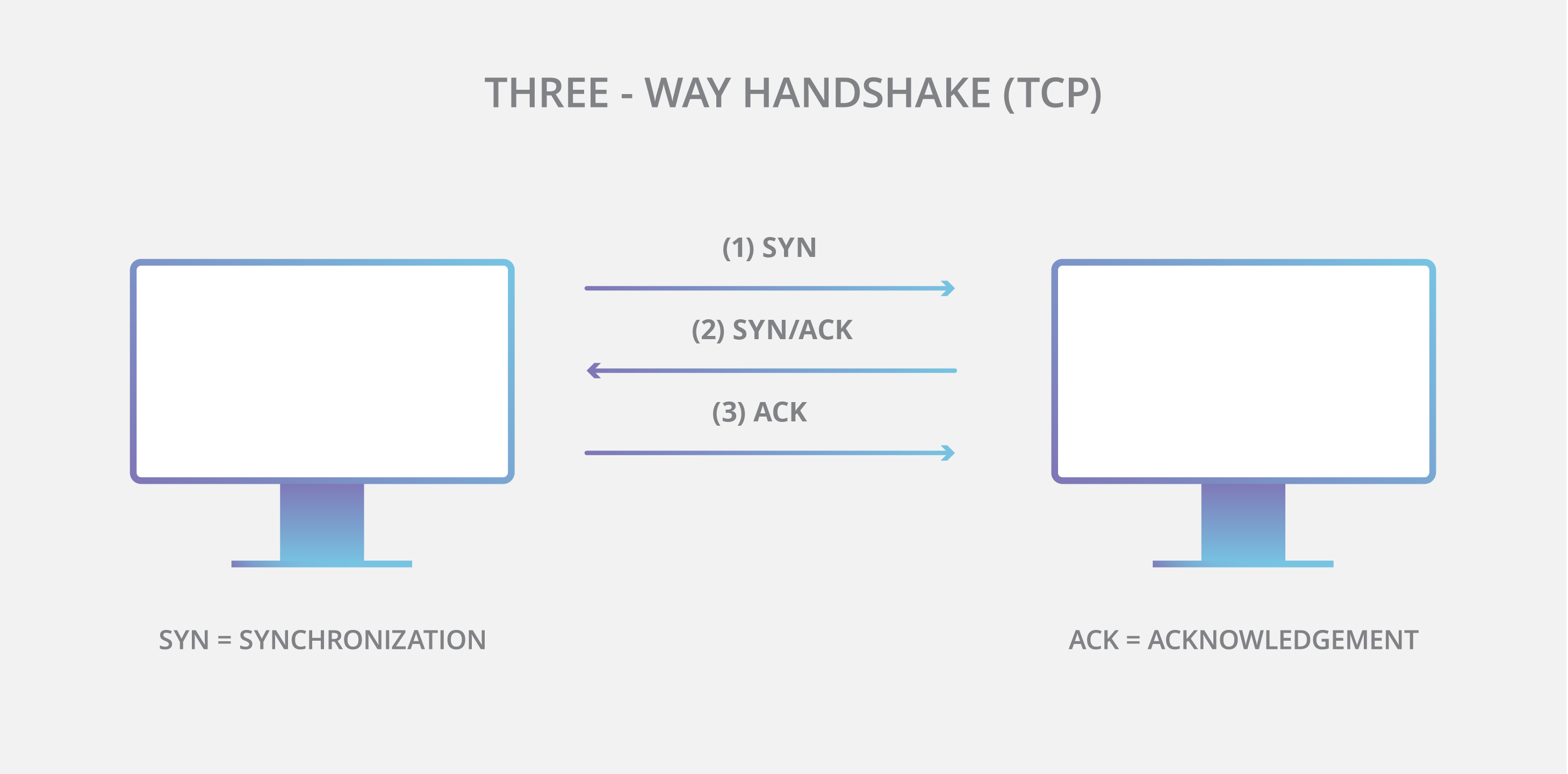

Now that the browser has the IP address for the URL entered by the user, it can now communicate with the server. In order to fetch information from the server, the browser first opens a TCP connection with the target server with the IP address from the DNS lookup query.

What is TCP/IP?

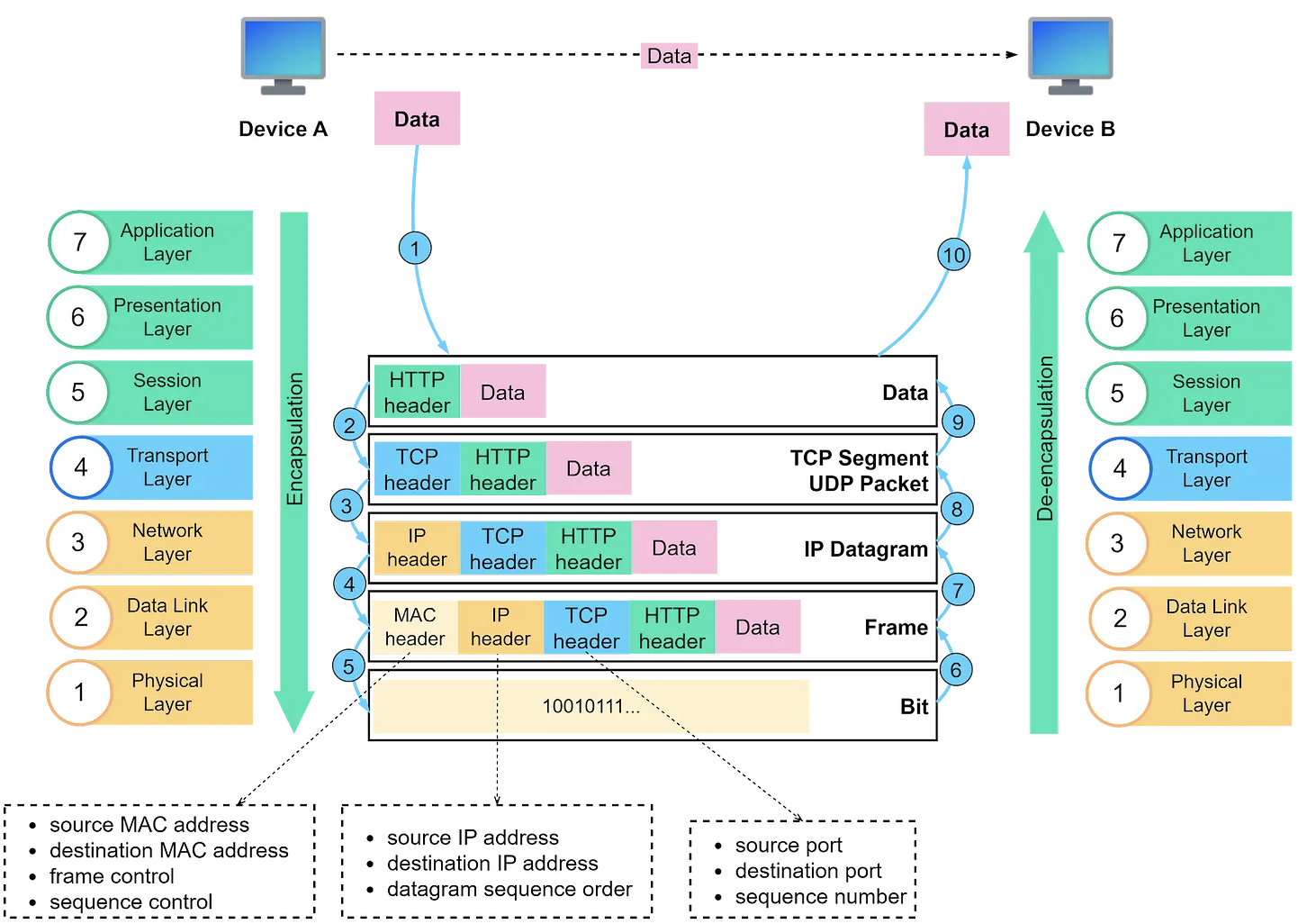

The Internet Protocol (IP) is the address system of the Internet and has the core function of delivering packets of information from a source device to a target device. IP is the primary way in which network connections are made, and it establishes the basis of the Internet.

IP does not handle packet ordering or error checking. Such functionality requires another protocol, often the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP).

IP is a connectionless protocol, which means that each unit of data is individually addressed and routed from the source device to the target device, and the target does not send an acknowledgement back to the source.

That’s where protocols such as TCP come in. TCP is used in conjunction with IP in order to maintain a connection between the sender and the target and to ensure packet order.

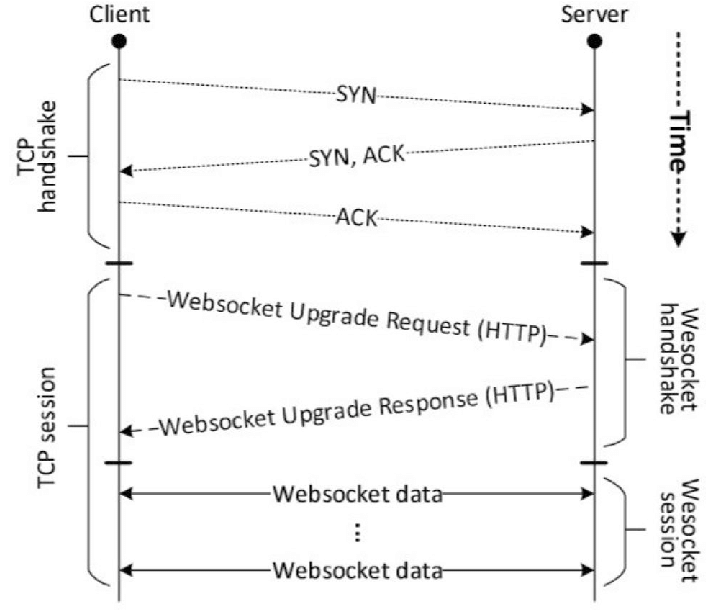

Handshake

When a message is sent over TCP, a connection is established and a 3-way handshake is made. First, the source sends an SYN “initial request” packet to the target server in order to start the dialogue. Then the target server sends a SYN-ACK packet to agree to the process. Lastly, the source sends an ACK packet to the target to confirm the process, after which the message contents can be sent.

The message is ultimately broken down into packets before each packet is sent out into the Internet, where it traverses a series of gateways before arriving at the target device where the group of packets are reassembled by TCP into the original contents of the email.

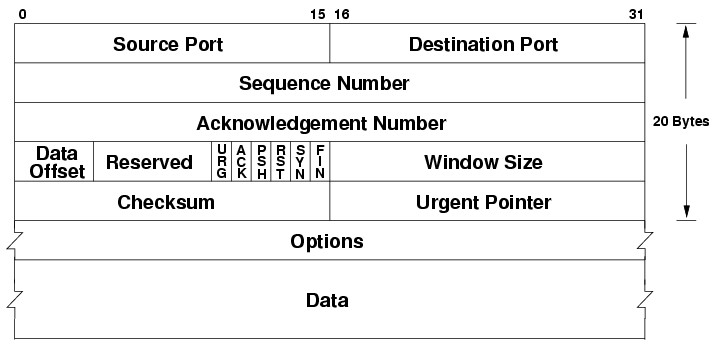

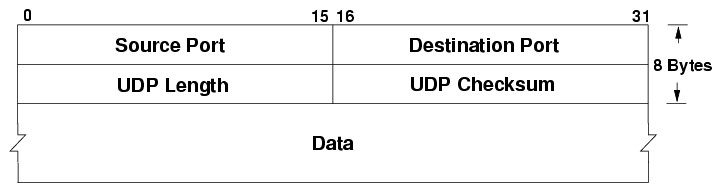

The recipient will send a message back to the sender for each packet, acknowledging that they’ve been received. Any packets not acknowledged by the recipient are sent again. Packets are checked for errors using a checksum, which is also included in the header.

NOTE The UDP protocol is also build on top of IP and the datagram structure is very similar to TCP/IP as shown below. The main difference is that its faster and simpler because there is no sequencing of datagrams and packets will not be resent.

Why is the handshake important?

TCP’s three-way handshake has two important functions:

- It makes sure that both sides know that they are ready to transfer data

- It also allows both sides to agree on the initial sequence numbers, which are sent and acknowledged (so there is no mistake about them) during the handshake.

TLS Handshake

Browser has now established a TCP/IP connection with the server and can we ready to start sending data? Nope! Though we have established connection, it is not protected and hence is at risk of being exploited upon by malicious actors. Imagine the risk if its bank application or anything with commercial implications.

What is TLS?

Transport Layer Security, or TLS, is a widely adopted security protocol designed to facilitate privacy and data security for communications over the Internet.

TLS evolved from Secure Socket Layers (SSL) which was originally developed by Netscape Communications Corporation in 1994 to secure web sessions. SSL 1.0 was never publicly released, whilst SSL 2.0 was quickly replaced by SSL 3.0 on which TLS is based.

It should be noted that TLS does not secure data on end systems. It simply ensures the secure delivery of data over the Internet, avoiding possible eavesdropping and/or alteration of the content.

TLS is normally implemented on top of TCP in order to encrypt Application Layer protocols such as HTTP, FTP, SMTP and IMAP, although it can also be implemented on UDP, DCCP and SCTP as well (e.g. for VPN and SIP-based application uses) and is known as Datagram Transport Layer Security (DTLS).

Why is TLS needed?

An unprotected TCP connection is susceptible to a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack. You can read more at [[Man In The Middle (MITM) attack]]

What does TLS do?

There are three main components to what the TLS protocol accomplishes: Encryption, Authentication, and Integrity.

- Encryption: hides the data being transferred from third parties.

- Authentication: ensures that the parties exchanging information are who they claim to be.

- Integrity: verifies that the data has not been forged or tampered with.

How does TLS work?

HTTPS uses an encryption protocol to encrypt communications. The protocol is called Transport Layer Security (TLS), although formerly it was known as Secure Sockets Layer (SSL).

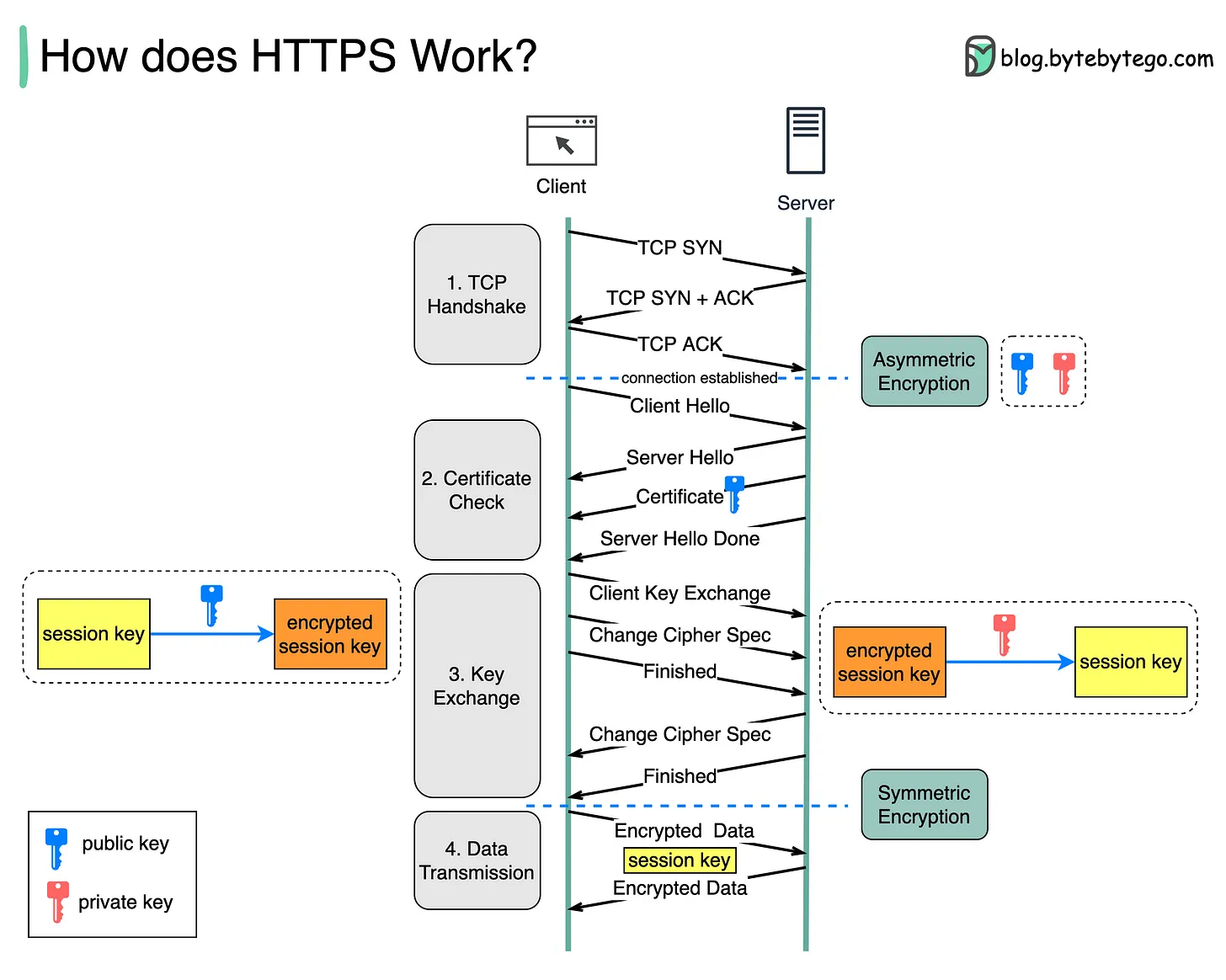

Step 1 - The client (browser) and the server establish a TCP connection.

Step 2 - The client sends a “client hello” to the server. The message contains a set of necessary encryption algorithms (cipher suites) and the latest TLS version it can support. The server responds with a “server hello” so the browser knows whether it can support the algorithms and TLS version.

The server then sends the SSL certificate to the client. The certificate contains the public key, hostname, expiry dates, etc. The client validates the certificate.

Step 3 - After validating the SSL certificate, the client generates a session key and encrypts it using the public key. The server receives the encrypted session key and decrypts it with the private key.

Step 4 - Now that both the client and the server hold the same session key (symmetric encryption), the encrypted data is transmitted in a secure bi-directional channel.

Why does HTTPS switch to symmetric encryption during data transmission?

There are two main reasons:

Security: The asymmetric encryption goes only one way. This means that if the server tries to send the encrypted data back to the client, anyone can decrypt the data using the public key.

Server resources: The asymmetric encryption adds quite a lot of mathematical overhead. It is not suitable for data transmissions in long sessions.

Making a HTTP request

What is HTTP?

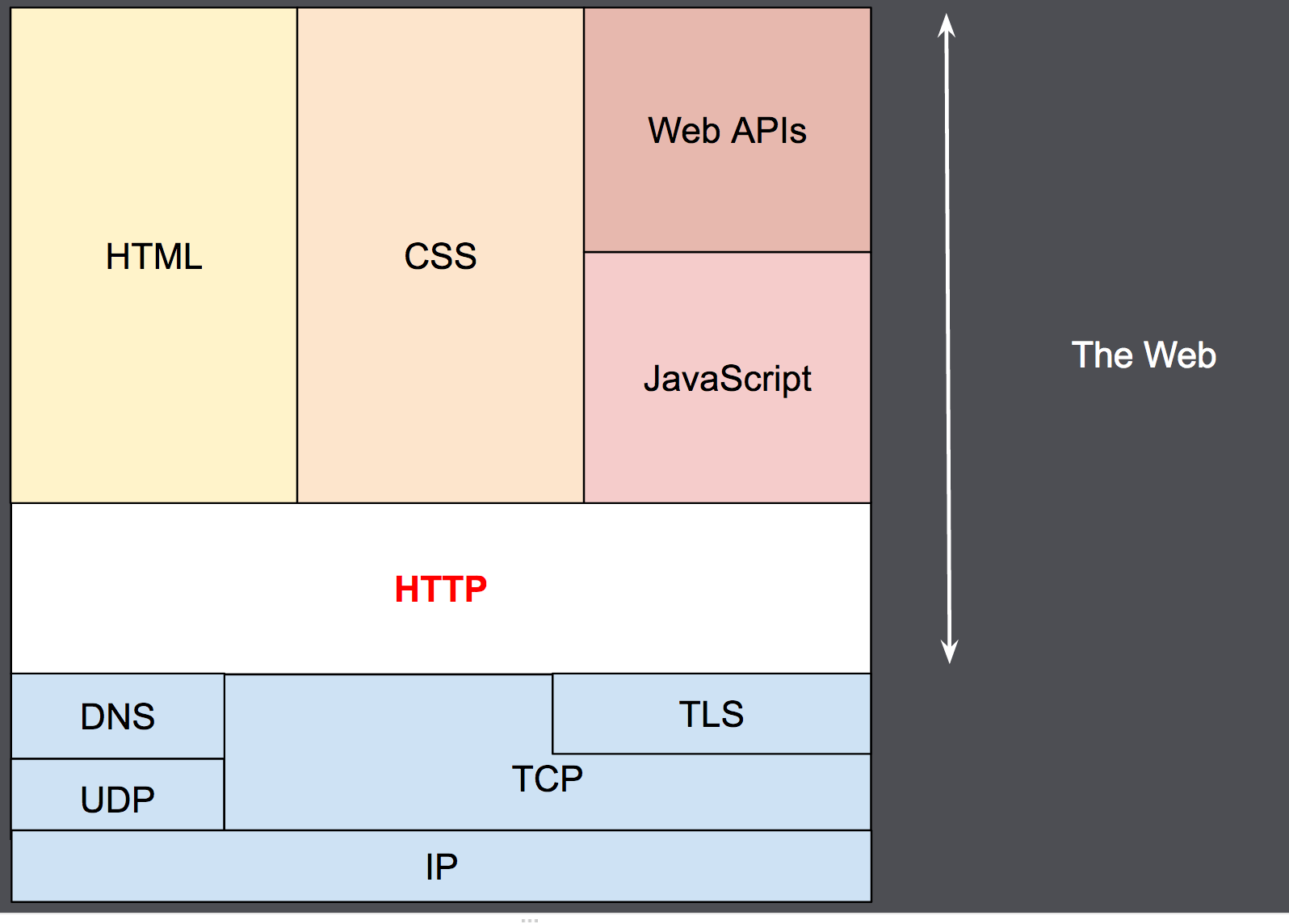

The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the foundation of the World Wide Web, and is used to load webpages using hypertext links. HTTP is an application layer protocol designed to transfer information between networked devices and runs on top of other layers of the network protocol stack. A typical flow over HTTP involves a client machine making a request to a server, which then sends a response message.

An HTTP request is the way Internet communications platforms such as web browsers ask for the information they need to load a website.

Components of HTTP based system

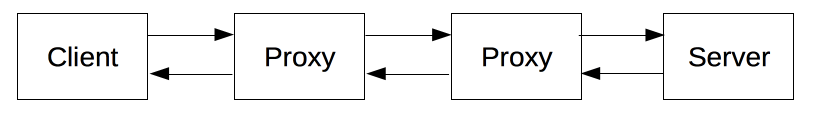

HTTP is a client-server protocol: requests are sent by one entity, the user-agent (or a proxy on behalf of it). Most of the time the user-agent is a Web browser, but it can be anything, for example, a robot that crawls the Web to populate and maintain a search engine index.

Each individual request is sent to a server, which handles it and provides an answer called the response. Between the client and the server there are numerous entities, collectively called proxies, which perform different operations and act as gateways or caches, for example.

Proxies may perform numerous functions:

- caching (the cache can be public or private, like the browser cache)

- filtering (like an antivirus scan or parental controls)

- load balancing (to allow multiple servers to serve different requests)

- authentication (to control access to different resources)

- logging (allowing the storage of historical information)

HTTP & Connection

A connection is controlled at the transport layer, and therefore fundamentally out of scope for HTTP. HTTP doesn’t require the underlying transport protocol to be connection-based; it only requires it to be reliable, or not lose messages.

Among the two most common transport protocols on the Internet, TCP is reliable and UDP isn’t. HTTP therefore relies on the TCP standard, which is connection-based.

HTTP Types & History

Invention of WWW

In 1989, while working at CERN, Tim Berners-Lee wrote a proposal to build a hypertext system over the internet. Initially called the Mesh, it was later renamed the World Wide Web during its implementation in 1990. Built over the existing TCP and IP protocols, it consisted of 4 building blocks:

- A textual format to represent hypertext documents, the HyperText Markup Language (HTML).

- A simple protocol to exchange these documents, the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP).

- A client to display (and edit) these documents, the first web browser called the WorldWideWeb.

- A server to give access to the document, an early version of httpd.

HTTP/0.9

HTTP/0.9 was extremely simple: requests consisted of a single line and started with the only possible method GET followed by the path to the resource. The full URL wasn’t included as the protocol, server, and port weren’t necessary once connected to the server.

The response was extremely simple, too: it only consisted of the file itself. Unlike subsequent evolutions, there were no HTTP headers. This meant that only HTML files could be transmitted. There were no status or error codes.

HTTP/1.0

- Versioning information was sent within each request (

HTTP/1.0was appended to theGETline). - A status code line was also sent at the beginning of a response. This allowed the browser itself to recognize the success or failure of a request and adapt its behavior accordingly. For example, updating or using its local cache in a specific way.

- The concept of HTTP headers was introduced for both requests and responses. Metadata could be transmitted and the protocol became extremely flexible and extensible.

- Documents other than plain HTML files could be transmitted thanks to the

Content-Typeheader.

HTTP/1.1

- A connection could be reused, which saved time. It no longer needed to be opened multiple times to display the resources embedded in the single original document.

- Pipelining was added. This allowed a second request to be sent before the answer to the first one was fully transmitted. This lowered the latency of the communication.

- Chunked responses were also supported.

- Additional cache control mechanisms were introduced.

- Content negotiation, including language, encoding, and type, was introduced. A client and a server could now agree on which content to exchange.

- Thanks to the

Hostheader, the ability to host different domains from the same IP address allowed server collocation.

HTTP for secure transmissions

The largest change to HTTP was made at the end of 1994. Instead of sending HTTP over a basic TCP/IP stack, the computer-services company Netscape Communications created an additional encrypted transmission layer on top of it: SSL.

To do this, they encrypted and guaranteed the authenticity of the messages exchanged between the server and client. SSL was eventually standardized and became TLS. During the same time period, it became clear that an encrypted transport layer was needed. The web was no longer a mostly academic network, and instead became a jungle where advertisers, random individuals, and criminals competed for as much private data as possible.

HTTP for complex applications

Tim Berners-Lee didn’t originally envision HTTP as a read-only medium. He wanted to create a web where people could add and move documents remotely—a kind of distributed file system.

In 2000, a new pattern for using HTTP was designed: representational state transfer (or REST). The API wasn’t based on the new HTTP methods, but instead relied on access to specific URIs with basic HTTP/1.1 methods.

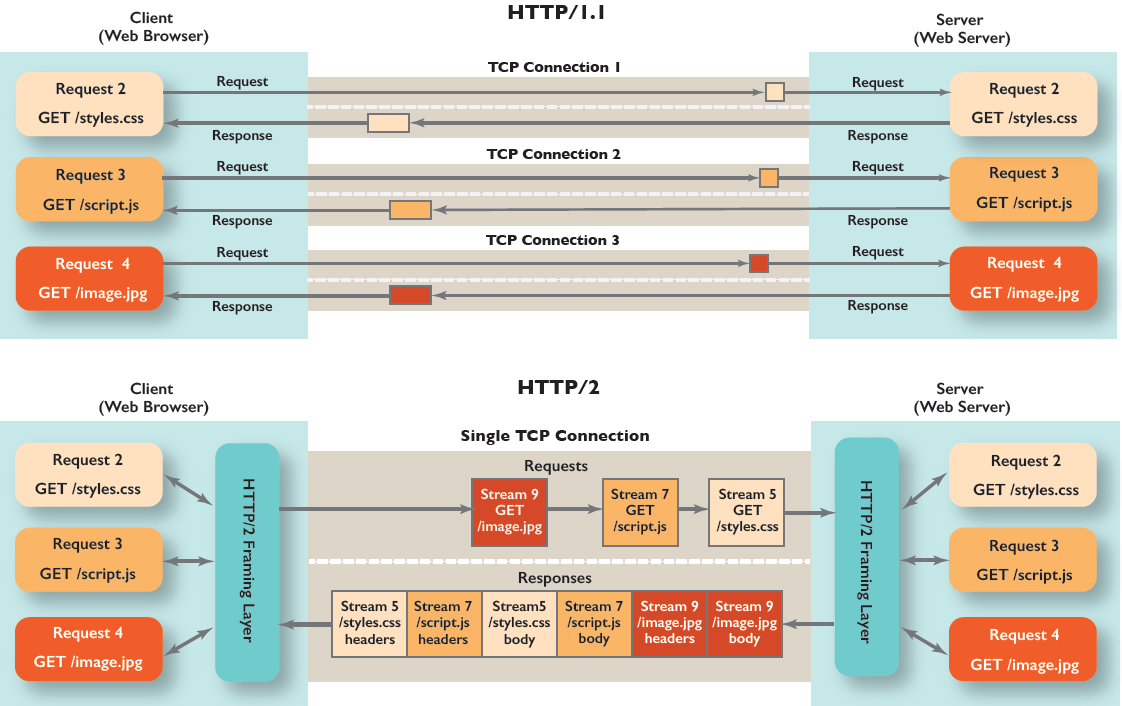

HTTP/2

Over the years, web pages became more complex. Much more data was transmitted over significantly more HTTP requests and this created more complexity and overhead for HTTP/1.1 connections.

The HTTP/2 protocol differs from HTTP/1.1 in a few ways:

- It’s a binary protocol rather than a text protocol. It can’t be read and created manually. Despite this hurdle, it allows for the implementation of improved optimization techniques.

- It’s a multiplexed protocol. Parallel requests can be made over the same connection, removing the constraints of the HTTP/1.x protocol.

- It compresses headers. As these are often similar among a set of requests, this removes the duplication and overhead of data transmitted.

- It allows a server to populate data in a client cache through a mechanism called the server push.

Not all types of HTTP requests can be pipelined: only idempotent methods, that is

GET,HEAD,PUTandDELETE, can be replayed safely.

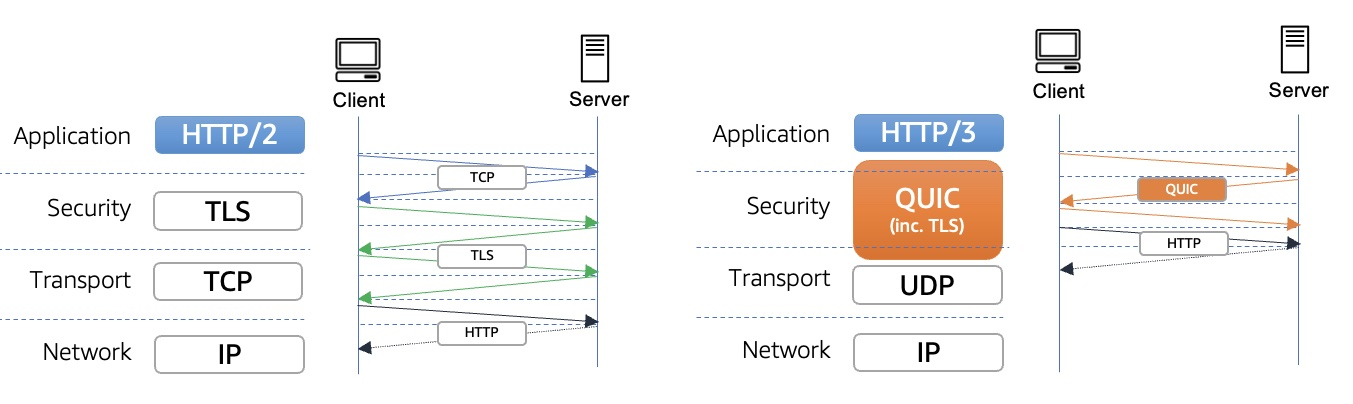

HTTP/3 - HTTP over QUIC

The next major version of HTTP, HTTP/3 has the same semantics as earlier versions of HTTP but uses QUIC instead of TCP for the transport layer portion. QUIC is designed to provide much lower latency for HTTP connections.

QUIC

QUIC is a multiplexed transport protocol implemented on UDP. It is used instead of TCP as the transport layer in HTTP/3. QUIC was designed to provide quicker setup and lower latency for HTTP connections. In particular:

In TCP, the initial TCP handshake is optionally followed by a TLS handshake, which must complete before data can be transmitted. Since TLS is almost ubiquitous now, QUIC integrates the TLS handshake into the initial QUIC handshake, reducing the number of messages that must be exchanged during setup.

HTTP/2 is a multiplexed protocol, allowing multiple simultaneous HTTP transactions. However, the transactions are multiplexed over a single TCP connection, meaning that packet loss and subsequent retransmissions at the TCP layer can block all transactions. QUIC avoids this by running over UDP and implementing packet loss detection and retransmission separately for each stream, meaning that packet loss only blocks the particular stream whose packets were lost.

Layers above HTTP

REST

History

Given the new, rapidly growing demand and use case for the Web, many working groups got formed to develop the web further. One of these groups was the HTTP Working Group, which worked on the new requirements to support the future of the growing World Wide Web. One member of the HTTP Working Group was Roy Thomas Fielding, who simultaneously worked on a broader architectural concept called Representational State Transfer — REST.

So REST architecture and HTTP 1.1 protocol are independent of each other, but the HTTP 1.1 protocol was built to be the ideal protocol to follow the principles and constraints of REST.

Definition

REST stands for REpresentational State Transfer.

It means when a RESTful API is called, the server will transfer to the client a representation of the state of the requested resource. The representation of the state can be in a JSON format, and probably for most APIs, this is indeed the case. It can also be in XML or HTML format.

REST doesn’t add any functionality onto HTTP but is an architectural style alongside HTTP. REST is a set of ‘rules’ (or ‘constraints’). defining the characteristics of the optimal application for a distributed hypermedia system, like the World Wide Web.

Architectural Constraints

REST defines 6 architectural constraints which make any web service – a truly RESTful API.

Uniform Interface (Standards)

Identification of resources - The REST style is centred around resources. This is unlike SOAP and other RPC styles that are modelled around procedures (or methods) and a resource is basically anything that can be named or resources are usually the entities from the business domain.

Manipulation of resources through these representations - This means that the client does not interact directly with the server’s resource. For example, we don’t allow the client to run SQL statements against our database tables. It just means that we show the resource’s data (i.e. state) in a neutral format.

Self-descriptive messages - The third constraint in the Uniform Interface is that each message (i.e. request/response) must include enough information for the receiver to understand it in isolation. Each message must have a media type (for example application/json or application/xml) that tells the receiver how the message should be parsed.

HATEOAS - Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State (HATEOAS) sounds a bit overwhelming, but in reality, it’s a simple concept. A web page is an instance of application state, hypermedia is text with hyperlinks. The hypermedia drives the application state. In other words, we click on links to move to new pages (i.e. application states). So when you are surfing the web, you are using hypermedia as the engine of application state! This means that HATEOAS should guide a user through the interface by offering control alongside the data.

Client-server

This essentially means that client application and server application must be able to evolve separately without any dependency on each other and I mean it should follow separation of concerns.

Stateless

Roy fielding got inspiration from HTTP, so it reflects in this constraint. Make all client-server interaction stateless. The server will not store anything about latest HTTP request client made. It will treat each and every request as new and it should not depend on any previous information shared between the two. No session, no history.

If client application needs to be a stateful application for the end user, where user logs in once and do other authorized operations thereafter, then each request from the client should contain all the information necessary to service the request – including authentication and authorization details.

No client context shall be stored on the server between requests. The client is responsible for managing the state of the application.

Cacheable

In REST, each response can be labelled as cacheable or non-cacheable. The cached response can be used for the response of the request rather than asking the server so we can eliminate the communication between the server and client up to some degree.

Layered System

Components can’t see beyond immediate layer. REST allows you to use a layered system architecture where you deploy the APIs on server A, and store data on server B and authenticate requests in Server C. These servers might provide a security layer, a caching layer, a load-balancing layer, or other functionality. Those layers should not affect the request or the response.

Real-time communication protocols

Websockets

WebSocket is a duplex protocol used mainly in the client-server communication channel. It’s bidirectional in nature which means communication happens to and fro between client-server. WebSocket uses a unified TCP connection and needs one party to terminate the connection.

WebSocket need support from HTTP to initiate the connection.

Websockets are typically used in the following use cases:

- Developing a real-time web application

- Basically cases where there is a need to continually display updated data to the client

- Ex: Trading applications, social media home pages etc

- Creating a chat application

- For operations like a one-time exchange and publishing/broadcasting the messages

- Ex: WhatsApp, Twitter etc

- Gaming application

- In online gaming the server is unremittingly receiving the data, without asking for UI refresh

XMPP

Short for Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol, XMPP is an open standard that supports near-real-time chat and instant messaging by governing the exchange of XML data over a network.

XMPP emerged in 1998 as the framework behind Jabber, an open-source, decentralized instant messaging alternative to now-defunct proprietary chat services like AIM and MSN Messenger.

Some of the key highlights of XMPP:

- Decentralized Hosting

- XMPP is decentralized, meaning that anyone can spin up, maintain, and operate their own XMPP server

- In this way, XMPP is similar to email.

- Asynchronous Push Messaging

- XMPP lets users’ devices send messages asynchronously, meaning you can send multiple messages in a row without waiting for a response, and two users don’t have to be online at the same time in order to message each other.

- Client-Server Architecture

- XMPP works by passing small, structured chunks of XML data between endpoints (clients) via intermediary servers.

- Each client has a unique name, similar to an email address, that the server uses to identify and route messages.

- Security

- XMPP allows developers to set up a separate storage server which can have its own encryption and security standards

XMPP can use HTTP or Websockets for transport. Using XMPP with WebSockets presents limitations, however, as XMPP is not optimized for transport speed like WebSockets. XMPP also doesn’t support binary data transmission - only textual data in an XML format.

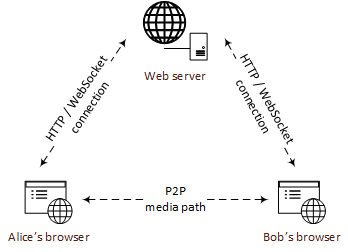

WebRTC

Web Real-Time Communication (WebRTC) is a framework that enables you to add real time communication (RTC) capabilities to your web and mobile applications.

WebRTC allows the transmission of arbitrary data (video, voice, and generic data) in a peer-to-peer fashion.

WebRTC consists of several interrelated APIs. Here are the key ones:

RTCPeerConnection. Allows you to connect to a remote peer, maintain and monitor the connection, and close it once it has fulfilled its purpose.RTCDataChannel. Provides a bi-directional network communication channel that allows peers to transfer arbitrary data.MediaStream. Designed to let you access streams of media from local input devices like cameras and microphones. It serves as a way to manage actions on a data stream, like recording, sending, resizing, and displaying the stream’s content.

WebRTC is a good choice for the following use cases:

- Audio and video communications, such as video calls, video chat, video conferencing, and browser-based VoIP.

- File sharing apps.

- Screen sharing apps.

- Broadcasting live events (such as sports events).

- IoT devices (e.g., drones or baby monitors streaming live audio and video data).

RPC

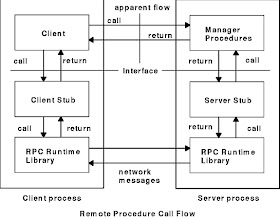

RPC is a request–response software communication protocol.

An RPC is initiated by the client, which sends a request message to a known remote server to execute a specified procedure with supplied parameters. The remote server sends a response to the client, and the application continues its process.

Sequence of events

- The client calls the client stub. The call is a local procedure call, with parameters pushed on to the stack in the normal way.

- The client stub packs the parameters into a message and makes a system call to send the message. Packing the parameters is called marshalling.

- The client’s local operating system sends the message from the client machine to the server machine.

- The local operating system on the server machine passes the incoming packets to the server stub.

- The server stub unpacks the parameters from the message. Unpacking the parameters is called unmarshalling.

- Finally, the server stub calls the server procedure. The reply traces the same steps in the reverse direction.

When to use RPC?

Simplicity and Tight Coupling: RPC is generally more straightforward and easier to implement when you have a relatively simple, well-defined API and tight coupling between the client and server. Ex: Internal service/component communication.

Strong Typing: RPC frameworks often provide strong typing support, which can be advantageous when you want to ensure data consistency and avoid type-related errors in your communication.

Remote Method Invocation: If your application primarily revolves around invoking remote methods and procedures on the server, using RPC might be a natural fit.

Performance and Efficiency: RPC can be more performant and efficient than REST in certain cases due to its lower overhead and direct method invocation.

When to use REST?

Scalability and Loose Coupling: REST’s stateless nature and loose coupling make it a better choice for distributed systems that require scalability and interoperability. RESTful APIs are independent of the underlying implementation, allowing clients and servers to evolve independently.

Standardization and Interoperability: REST is based on standard HTTP methods and status codes, making it easier to work with different client platforms and server implementations. It promotes better interoperability between systems.

Resource-Oriented Design: If your application’s data and functionalities are organised as resources, REST’s resource-oriented design can be more intuitive and aligned with HTTP principles.

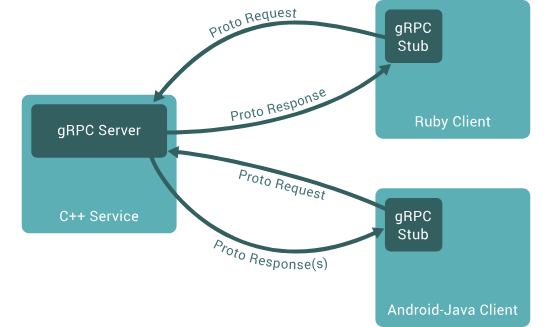

gRPC

gRPC is a modern open source high performance Remote Procedure Call (RPC) framework that can run in any environment. It can efficiently connect services in and across data centers with pluggable support for load balancing, tracing, health checking and authentication.

In gRPC, a client application can directly call a method on a server application on a different machine as if it were a local object, making it easier for you to create distributed applications and services.

By default, gRPC uses Protocol Buffers, Google’s mature open source mechanism for serializing structured data.

Why use gRPC?

Performance and Efficiency: gRPC’s use of Protocol Buffers (protobuf) for data serialization results in a compact and efficient binary representation of data. This reduces payload size, leading to faster data transmission and reduced network overhead, making it more performant compared to RESTful APIs using JSON.

Strong Typing and Code Generation: With gRPC’s strong typing, developers can define their APIs using protocol buffers with specific data structures and operations. This allows automatic code generation for client and server APIs in various programming languages, promoting type safety and improving development productivity.

Bidirectional Streaming: gRPC supports bidirectional streaming, enabling both clients and servers to send multiple messages in a single connection. This is particularly useful in real-time applications like chat, video streaming, gaming, and collaborative environments.

Scalability and Concurrency: gRPC’s bidirectional streaming, asynchronous nature, and efficient handling of multiple requests over a single connection contribute to improved scalability and performance, making it suitable for high-concurrency and large-scale distributed systems.

RPC in Google

In general, Google tends to use REST for public APIs because of its simplicity, standardization, and compatibility with HTTP. RESTful APIs are well-suited for scenarios where interoperability with various programming languages and platforms is essential, as they rely on standard HTTP methods and can be accessed using standard HTTP clients.

It’s worth noting that while Google uses REST in public-facing APIs, they may also utilize gRPC and other communication protocols extensively within their internal infrastructure for efficient and high-performance communication between microservices and backend components.

GraphQL

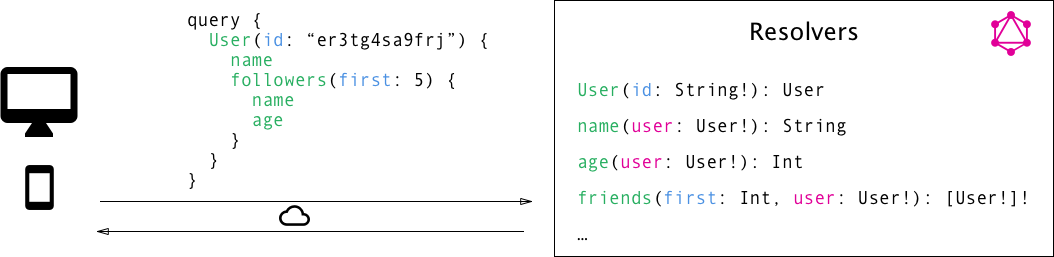

GraphQL is a query language for APIs and a runtime for fulfilling those queries with your existing data.

Core benefits of GraphQL

- Ask for what you need get exactly that

- Get many resources in a single request

- Describe what’s possible with a type system

- Evolve your API without versions

- Bring your own data and code

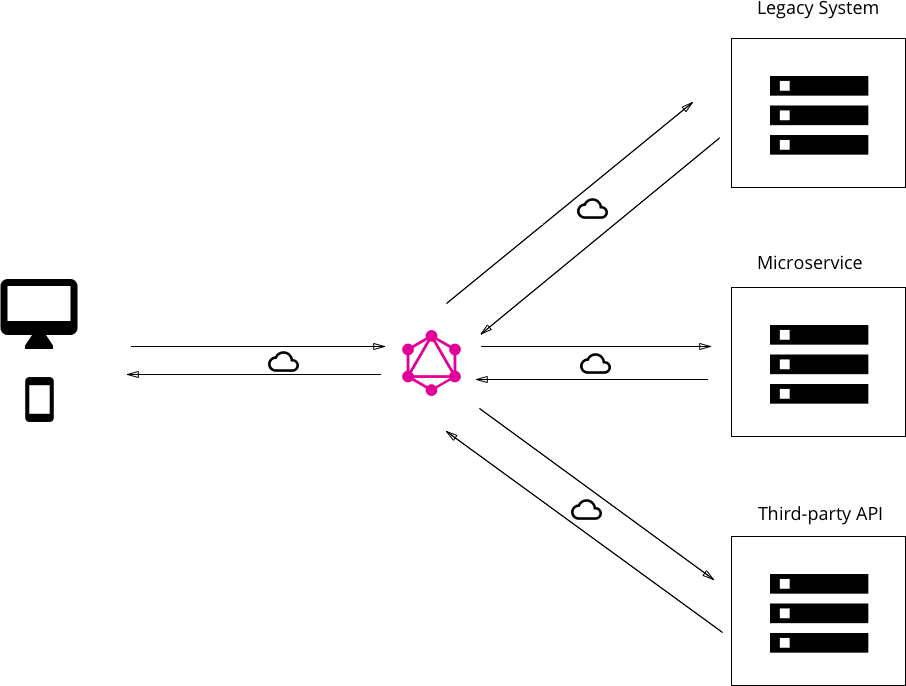

Architecture

Render the response from server

When a browser receives a response from the server, it follows a series of steps to render and display the content to the user. Here’s a simplified overview of the process:

Parsing the HTML: The browser begins by parsing the received HTML document. It breaks down the HTML code into a Document Object Model (DOM) tree, representing the structure of the web page.

Building the Render Tree: The browser combines the DOM tree with the CSS stylesheets associated with the web page to create a Render Tree. The Render Tree contains information about how each element should be rendered, including their visual properties like size, position, and visibility.

Layout: The browser performs a layout operation, also known as reflow or layout, to determine the exact position and size of each element on the web page. It calculates the dimensions based on the CSS box model and any additional constraints.

Painting: After the layout is complete, the browser goes through the process of painting, which involves drawing the pixels on the screen corresponding to the elements in the Render Tree. This step includes rendering the backgrounds, text, images, borders, and other visual elements.

Rendering and Display: The browser displays the painted content on the user’s screen. The rendered web page becomes visible, and the user can interact with the displayed elements such as clicking links, submitting forms, or interacting with embedded media.

Handling Scripts and Interactivity: If the web page contains JavaScript code, the browser executes the scripts to add interactivity and dynamic behavior to the page. JavaScript can manipulate the DOM, make additional requests to the server, update the content dynamically, or handle user interactions.

It’s worth noting that this process happens in parallel and is optimized for performance. Browsers use techniques like incremental rendering, caching, and prioritization to ensure a smooth and efficient user experience.

Additionally, modern web technologies like AJAX, asynchronous requests, and client-side rendering allow for more dynamic and interactive web applications where parts of the page can be updated without reloading the entire document.

Overall, the rendering process involves parsing and interpreting the received HTML, combining it with CSS stylesheets, calculating layouts, painting pixels, and finally displaying the rendered content to the user.