Python Mappings

Reference

Modern dict syntax

An example of dict Comprehensions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

>>> codes = [

>>> ('TN','TamilNadu'),

>>> ('KL','Kerala'),

>>> ('TS','Telengana'),

>>> ('KA','Karnataka'),

>>> ]

>>> codes_dict = {code: state for code, state in codes}

This above example can be extended to sort/filter codes variable similar to how we did list comprehensions.

Unpacking works in a similar way to lists as well with a small change.

1

2

3

4

5

>>> def dump(**kwargs):

... return kwargs

...

>>> dump(**{'x': 1}, y=2, **{'z': 3})

{'x': 1, 'y': 2, 'z': 3}

Though dict enforce it by default, ensure that the keys are unique. Also for dict to be unpacked as method arguments the keys need to be strings.

We can also merge mapping with the | operator as shown below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

>>> d1 = {'a': 1, 'b': 3}

>>> d2 = {'a': 2, 'b': 4, 'c': 6}

>>> d1 | d2

{'a': 2, 'b': 4, 'c': 6}

>>> d1 |= d2 # Inplace update of d1

Pattern Matching with Mappings

The match/case statement supports subjects that are mapping objects. Patterns for mappings look like dict literals, but they can match instances of any actual or virtual subclass of collections.abc.Mapping

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

def get_creators(record: dict) -> list:

match record:

case {'type': 'book', 'api': 2, 'authors': [*names]}:

return names

case {'type': 'book', 'api': 1, 'author': name}:

return [name]

case {'type': 'book'}:

raise ValueError(f"Invalid 'book' record: {record!r}")

case {'type': 'movie', 'director': name}:

return [name]

case _:

raise ValueError(f'Invalid record: {record!r}')

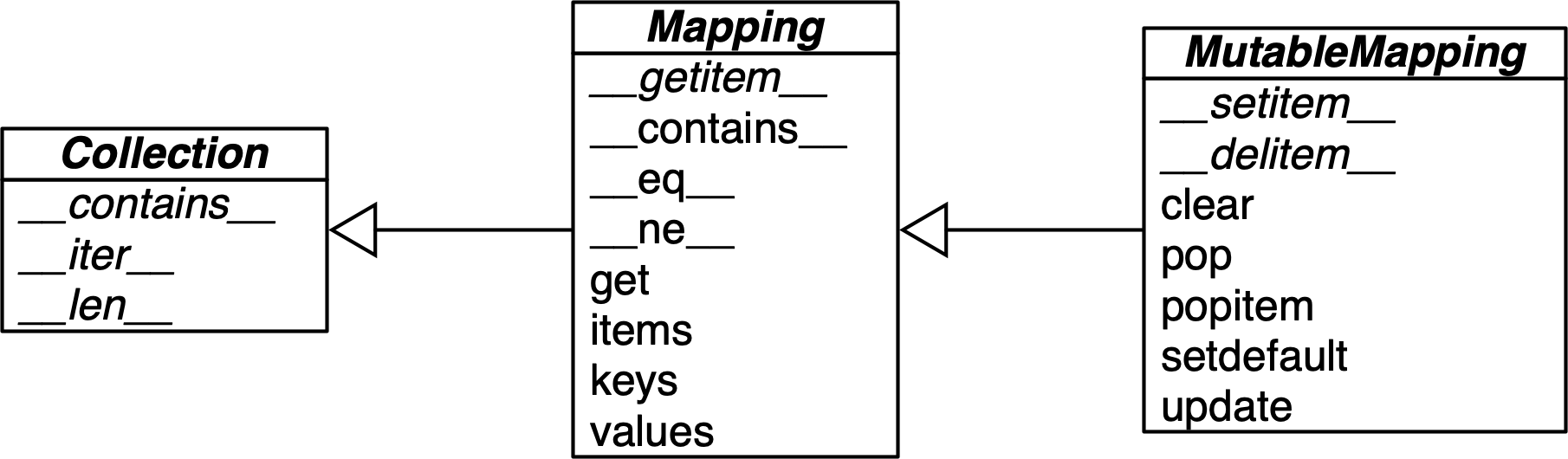

Standard API of Mapping Types

The collections.abc module provides the Mapping and MutableMapping ABCs describing the interfaces of dict and similar types.

1

2

3

4

5

>>> my_dict = {}

>>> isinstance(my_dict, abc.Mapping)

True

>>> isinstance(my_dict, abc.MutableMapping)

True

To implement a custom mapping, it’s easier to extend collections.UserDict, or to wrap a dict by composition, instead of subclassing these ABCs. The collections.UserDict class and all concrete mapping classes in the standard library encapsulate the basic dict in their implementation, which in turn is built on a hash table. Therefore, they all share the limitation that the keys must be hashable (the values need not be hashable, only the keys).

What is Hashable?

An object is hashable if it has a hash code which never changes during its lifetime (it needs a

__hash__()method), and can be compared to other objects (it needs an__eq__()method). Hashable objects which compare equal must have the same hash code.

Numeric types and flat immutable types str and bytes are all hashable. Container types are hashable if they are immutable and all contained objects are also hashable. A frozenset is always hashable, because every element it contains must be hashable by definition. A tuple is hashable only if all its items are hashable.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

>>> tt = (1, 2, (30, 40))

>>> hash(tt)

8027212646858338501

>>> tl = (1, 2, [30, 40])

>>> hash(tl)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'

>>> tf = (1, 2, frozenset([30, 40]))

>>> hash(tf)

-4118419923444501110

An interesting information around dict APIs is the way d.update(m) handles its first argument m is a prime example of duck typing:

- it first checks whether

mhas akeysmethod and, if it does, assumes it is a mapping. - Otherwise,

update()falls back to iterating overm, assuming its items are(key, value)pairs. - The constructor for most Python mappings uses the logic of

update()internally, which means they can be initialized from other mappings or from any iterable object producing(key, value)pairs.

Automatic Handling of Missing Keys

Using <dict>.setdefault

There is a better way to read a key & set a default if its missing to the dict

1

2

3

4

5

6

>>> my_dict.setdefault(key, []).append(new_value)

>>> # Same as

>>> if key not in my_dict:

my_dict[key] = []

my_dict[key].append(new_value)

Using collections.defaultdict

Another option which handles this without explicit intervention is defaultdict. A collections.defaultdict instance creates items with a default value on demand whenever a missing key is searched using d[k] syntax.

Here is how it works: when instantiating a defaultdict, you provide a callable to produce a default value whenever __getitem__ is passed a nonexistent key argument.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

"""Build an index mapping word -> list of occurrences"""

import collections

import re

import sys

WORD_RE = re.compile(r'\w+')

index = collections.defaultdict(list)

with open(sys.argv[1], encoding='utf-8') as fp:

for line_no, line in enumerate(fp, 1):

for match in WORD_RE.finditer(line):

word = match.group()

column_no = match.start() + 1

location = (line_no, column_no)

index[word].append(location)

## display in alphabetical order

for word in sorted(index, key=str.upper):

print(word, index[word])

The above examples:

- Creates a

defaultdictwith thelistconstructor asdefault_factory. - If

wordis not initially in theindex, thedefault_factoryis called to produce the missing value, which in this case is an emptylistthat is then assigned toindex[word]and returned, so the.append(location)operation always succeeds.

The mechanism that makes defaultdict work by calling default_factory is the __missing__ special method, a feature that we discuss next.

Using __missing__ method

This method is not defined in the base dict class, but dict is aware of it: if you subclass dict and provide a __missing__ method, the standard dict.__getitem__ will call it whenever a key is not found, instead of raising KeyError.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

class StrKeyDict0(dict):

def __missing__(self, key):

if isinstance(key, str):

raise KeyError(key)

return self[str(key)]

def get(self, key, default=None):

try:

return self[key]

except KeyError:

return default

def __contains__(self, key):

return key in self.keys() or str(key) in self.keys()

In the above example:

StrKeyDict0inherits fromdict.- The

getmethod delegates to__getitem__by using theself[key]notation; that gives the opportunity for our__missing__to act. - If a

KeyErrorwas raised,__missing__already failed, so we return thedefault. containsis updated to search for unmodified key (the instance may contain non-strkeys), then for astrbuilt from the key.- operation

k in dcalls it, but the method inherited fromdictdoes not fall back to invoking__missing__

- operation

If your subclass implements __getitem__, get, and __contains__, then you can make those methods use __missing__ or not, depending on your needs. You must be careful when subclassing standard library mappings to use __missing__, because the base classes support different behaviors by default.

Variations of dict

collections.OrderedDict- As of python

3.6, the built-indictkeeps the keys ordered so the most common reason to userOrderedDictwould be for backward compatibility. - Also ordering related operations are optimized in the case of

OrderedDict(like LRU cache) since it’s optimized for it

- As of python

collections.ChainMap- It holds a list of mappings that can be searched as one. The lookup is performed on each input mapping in the order it appears in the constructor call, and succeeds as soon as the key is found in one of those mappings.

- Updates or insertions to a

ChainMaponly affect the first input mapping. ChainMapis useful to implement interpreters for languages with nested scopes, where each mapping represents a scope context, from the innermost enclosing scope to the outermost scope.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

>>> d1 = dict(a=1, b=3)

>>> d2 = dict(a=2, b=4, c=6)

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> chain = ChainMap(d1, d2)

>>> chain['a']

1

>>> chain['c']

6

>>> chain['c'] = -1

>>> d1

{'a': 1, 'b': 3, 'c': -1}

>>> d2

{'a': 2, 'b': 4, 'c': 6}

import builtins

pylookup = ChainMap(locals(), globals(), vars(builtins))

collections.Counter- A mapping that holds an integer count for each key. Updating an existing key adds to its count.

Counterimplements the+and-operators to combine tallies, and other useful methods such asmost_common([n]), which returns an ordered list of tuples with the n most common items and their counts.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

>>> ct = collections.Counter('abracadabra')

>>> ct

Counter({'a': 5, 'b': 2, 'r': 2, 'c': 1, 'd': 1})

>>> ct.update('aaaaazzz')

>>> ct

Counter({'a': 10, 'z': 3, 'b': 2, 'r': 2, 'c': 1, 'd': 1})

>>> ct.most_common(3)

[('a', 10), ('z', 3), ('b', 2)]

shelve.Shelf- The

shelvemodule in the standard library provides persistent storage for a mapping of string keys to Python objects serialized in thepicklebinary format. - The curious name of

shelvemakes sense when you realize that pickle jars are stored on shelves.

- The

Subclassing UserDict instead of dict

The main reason why it’s better to subclass UserDict rather than dict is that the built-in has some implementation shortcuts that end up forcing us to override methods that we can just inherit from UserDict with no problems.

Note that UserDict does not inherit from dict, but uses composition: it has an internal dict instance, called data, which holds the actual items. This avoids undesired recursion when coding special methods like __setitem__, and simplifies the coding of __contains__ etc.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

import collections

class StrKeyDict(collections.UserDict):

def __missing__(self, key):

if isinstance(key, str):

raise KeyError(key)

return self[str(key)]

def __contains__(self, key):

return str(key) in self.data

def __setitem__(self, key, item):

self.data[str(key)] = item

Immutable Mappings

The mapping types provided by the standard library are all mutable, but you may need to prevent users from changing a mapping by accident.

The types module provides a wrapper class called MappingProxyType, which, given a mapping, returns a mappingproxy instance that is a read-only but dynamic proxy for the original mapping. This means that updates to the original mapping can be seen in the mappingproxy, but changes cannot be made through it.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

>>> from types import MappingProxyType

>>> d = {1: 'A'}

>>> d_proxy = MappingProxyType(d)

>>> d_proxy

mappingproxy({1: 'A'})

>>> d_proxy[1]

'A'

>>> d_proxy[2] = 'x'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'mappingproxy' object does not support item assignment

>>> d[2] = 'B'

>>> d_proxy

mappingproxy({1: 'A', 2: 'B'})

>>> d_proxy[2]

'B'

>>>

Dictionary Views

The dict instance methods .keys(), .values(), and .items() return instances of classes called dict_keys, dict_values, and dict_items, respectively. These dictionary views are read-only projections of the internal data structures used in the dict implementation. They avoid the memory overhead of the equivalent Python 2 methods that returned lists duplicating data already in the target dict, and they also replace the old methods that returned iterators.

A view object is a dynamic proxy. If the source dict is updated, you can immediately see the changes through an existing view.

Sets

The syntax of set literals—{1}, {1, 2}, etc.—looks exactly like the math notation, with one important exception: there’s no literal notation for the empty set, so we must remember to write set().

Don’t forget that to create an empty

set, you should use the constructor without an argument:set(). If you write{}, you’re creating an emptydict

Literal set syntax like {1, 2, 3} is both faster and more readable than calling the constructor (e.g., set([1, 2, 3])). The latter form is slower because, to evaluate it, Python has to look up the set name to fetch the constructor, then build a list, and finally pass it to the constructor.

There is no special syntax to represent frozenset literals—they must be created by calling the constructor.

1

2

>>> frozenset(range(10))

frozenset({0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9})

Set Comprehensions also work they way you’d expect them to.

1

2

3

4

>>> from unicodedata import name

>>> {chr(i) for i in range(32, 256) if 'SIGN' in name(chr(i),'')}

{'§', '=', '¢', '#', '¤', '<', '¥', 'µ', '×', '$', '¶', '£', '©',

'°', '+', '÷', '±', '>', '¬', '®', '%'}

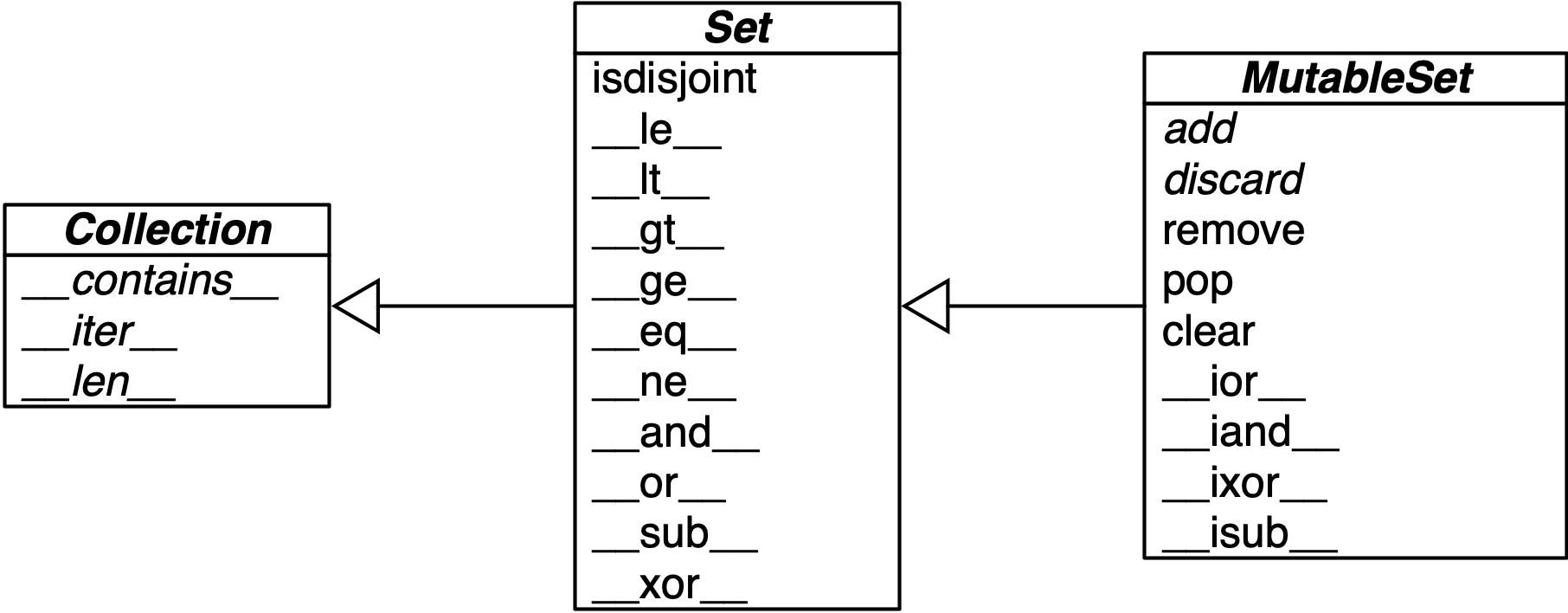

The figure below gives an overview of the methods you can use on mutable and immutable sets. Many of them are special methods that overload operators, such as & and >=.