Python Sequences

Reference

Build-in Sequences

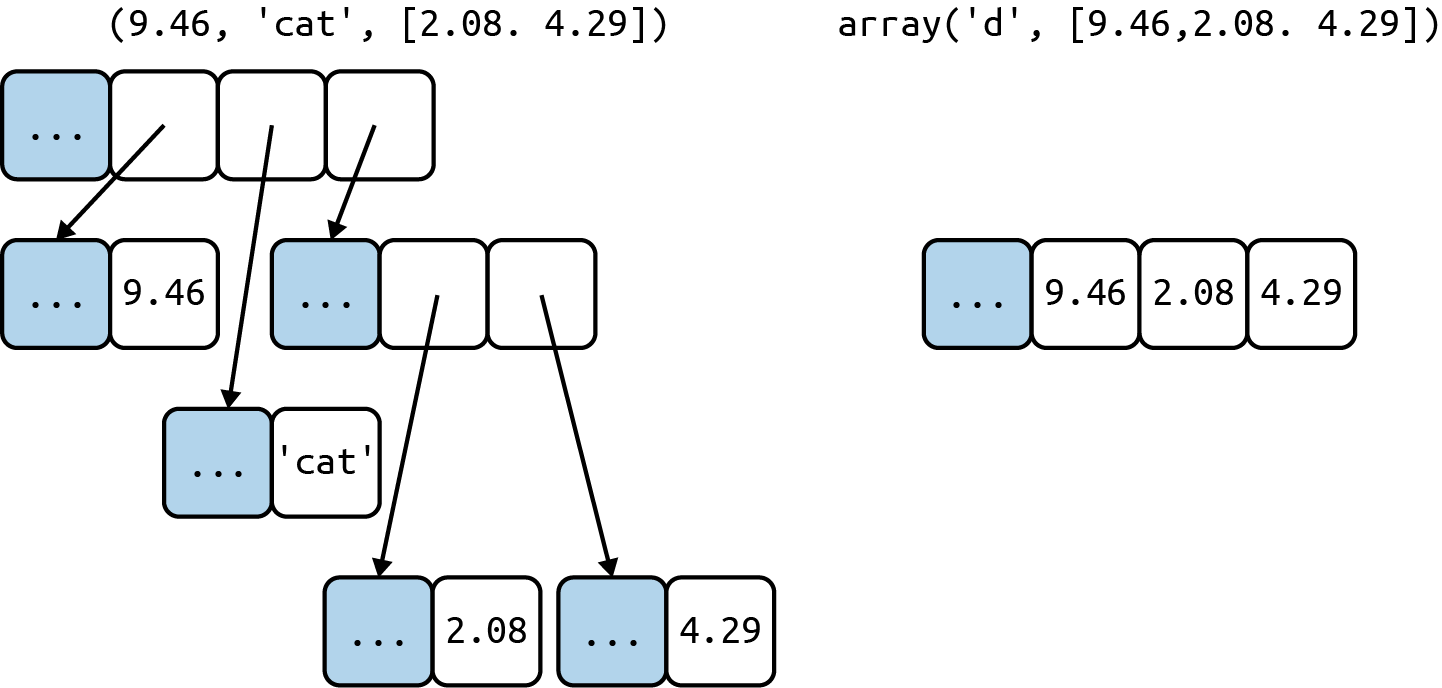

The Python standard library offers two build-in types to represent sequences:

- Container sequences - Can hold different datatypes including nested sequences. Eg.

list,tuple,deque - Flat Sequences - Hold items of only single type. Eg.

str,bytes,array.array

A container sequence holds the reference to the items it hold whereas the flat sequences hold the values of the items itself. Flat sequences are more compact but are limited to using primitive types like float, int & bytes.

Every Python object in memory has a header with metadata. The simplest Python object, a

float, has a value field and two metadata fields:

ob_refcnt: the object’s reference countob_type: a pointer to the object’s typeob_fval: a Cdoubleholding the value of thefloatOn a 64-bit Python build, each of those fields takes 8 bytes. That’s why an array of floats is much more compact than a tuple of floats: the array is a single object holding the raw values of the floats, while the tuple consists of several objects—the tuple itself and each

floatobject contained in it.

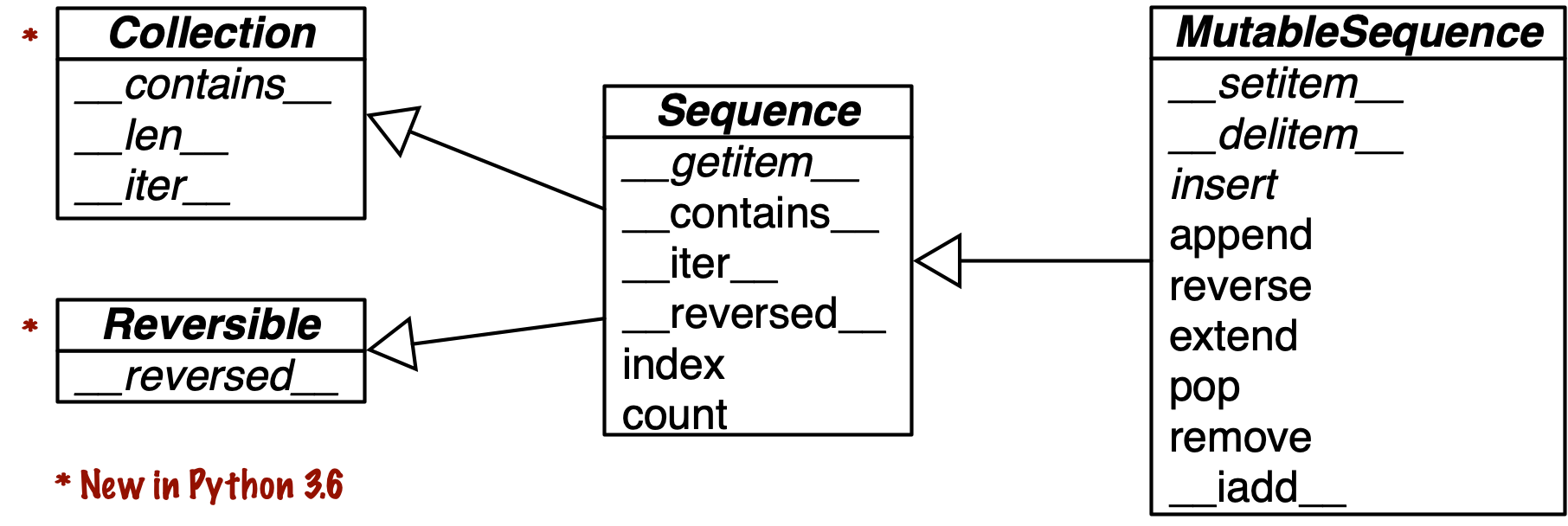

Another way of grouping lists is by mutability:

- Mutable sequences -

list,bytearray,array.array - Immutable sequences -

str,byte,tuple

The class diagram below shows how mutable sequences extend immutable functionalities.

List Comprehension & Generator Expressions

List comprehension is a concise way to create lists in Python. It allows you to generate a new list by applying an expression to each item in an existing iterable (such as a list, tuple, or range) and, optionally, to filter items using a condition.

Simple example of list comprehension which improves code readability.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

>>> # Conventional way

>>> array = []

>>> for i in range(5):

>>> array.append(i)

>>>

>>> # Better way

>>> array = [i for i in range(5)]

While the variables defined in listcomp have local scope in general, variables assigned with the “Walrus operator” := remain accessible after those comprehensions or expressions return—unlike local variables in a function.

1

2

3

4

5

>>> values = [last:= c for c in range(5)]

>>> last

>>> 5

>>> c

>>> <Throws Exception>

Listcomps vs map & filter

Listcomps are a far simpler alternative to the at times confusion map and filter commands.

1

2

3

4

>>> symbol = '$%#@!'

>>> non_ascii = [ord(s) for s in symbol if ord(s) > 127]

>>>

>>> non_ascii = list(filter(lambda c: c > 127, map(ord, symbols)))

Turns out that lictcomps are faster than using map and filter too - Speed Test Script

Generator Expressions

Listcomps are a one-trick pony: they build lists. To generate data for other sequence types, a genexp is the way to go. To initialize tuples, arrays, and other types of sequences, you could also start from a listcomp, but a genexp (generator expression) saves memory because it yields items one by one using the iterator protocol instead of building a whole list just to feed another constructor.

Genexps use the same syntax as listcomps, but are enclosed in parentheses rather than brackets.

1

2

>>> symbol = "@#%!"

>>> tuple(ord(s) for s in symbol)

Tuples

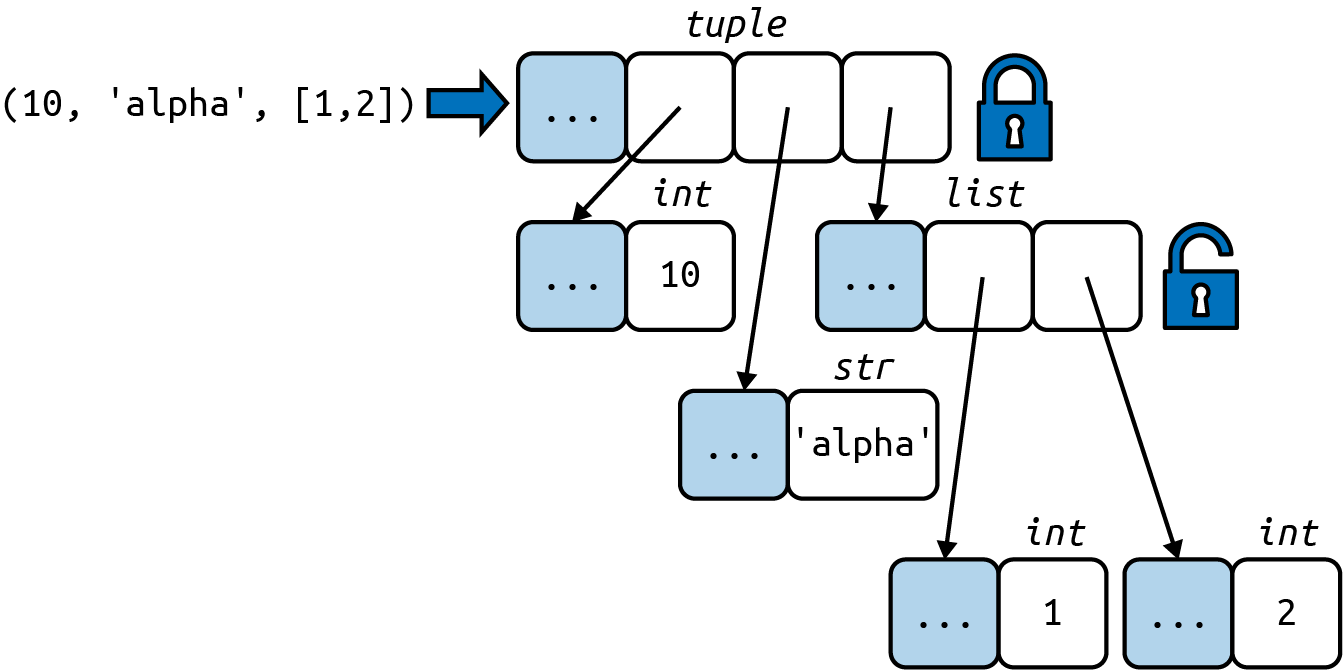

Tuples do double duty: they can be used as immutable lists and also as records with no field names.

Tuples as Records

Tuples hold records: each item in the tuple holds the data for one field, and the position of the item gives its meaning.

It’s easy to think of tuples as just lists which are immutable but when using a tuple as a collection of fields, the number of fields is fixed and order is important. Sorting in such cases would destroy the information that is given by the position of the data values.

Tuple as Immutable Lists

The Python interpreter and standard library make extensive use of tuples as immutable lists, and so should you. This brings two key benefits:

- Clarity

- When you see a

tuplein code, you know its length will never change.

- When you see a

- Performance

- A

tupleuses less memory than alistof the same length, and it allows Python to do some optimizations.

- A

The content of the tuple itself is immutable, but that only means the references held by the tuple will always point to the same objects. However, if one of the referenced objects is mutable—like a list—its content may change.

Tuples with mutable items can be a source of bugs. Despite this caveat, tuples are widely used as immutable lists. They offer some performance advantages as well.

Tuples tend to perform better than lists in almost every category:

- Tuples can be constant folded.

- Tuples can be reused instead of copied.

- Tuples are compact and don’t over-allocate.

- Tuples directly reference their elements.

Tuples of constants can be precomputed by Python’s peephole optimizer or AST-optimizer. Lists, on the other hand, get built-up from scratch:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

>>> from dis import dis

>>> dis(compile("(10, 'abc')", '', 'eval'))

1 0 LOAD_CONST 2 ((10, 'abc'))

3 RETURN_VALUE

>>> dis(compile("[10, 'abc']", '', 'eval'))

1 0 LOAD_CONST 0 (10)

3 LOAD_CONST 1 ('abc')

6 BUILD_LIST 2

9 RETURN_VALUE

Since a tuple’s size is fixed, it can be stored more compactly than lists which need to over-allocate to make append() operations efficient. This gives tuples a nice space advantage:

1

2

3

4

5

>>> import sys

>>> sys.getsizeof(tuple(iter(range(10))))

128

>>> sys.getsizeof(list(iter(range(10))))

200

Unpacking Sequences & Iterables

Unpacking is important because it avoids unnecessary and error-prone use of indexes to extract elements from sequences. Also, unpacking works with any iterable object as the data source even iterators (the only difference being that values are yielded one by one).

The most visible form of unpacking is parallel assignment

1

2

>>> coords = (36, 12)

>>> x, y = coords # Unpacking

Another way is by using * in front of an iterable object.

1

2

>>> params = (20,11)

>>> divmod(*params) # Unpacks params and passes it

You can also use * to grab excess items.

1

2

3

>>> a, *b, c = range(5)

>>> a, b, c

>>> (0, [1,2,3], 4)

You can use * for unpacking in sequence literals as well.

1

2

3

>>> nums = [*range(3), *range(4)]

>>> nums

>>> [0, 1, 2, 0, 1, 2, 3]

Pattern Matching with Sequences

The most visible new feature in Python 3.10 is the pattern matching with match/case statement. This can seems similar to switch..case but it’s much more. It can be used to unpack iterables (even nested or * for grabbing excess) and run a match exp for evaluation. This is called destructuring in Python, which is essentially a more advanced form of unpacking.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

>>> metro_areas = [

>>> ('Tokyo', 'JP', 36.933, (35.689722, 139.691667)),

>>> ('Delhi NCR', 'IN', 21.935, (28.613889, 77.208889)),

>>> ('Mexico City', 'MX', 20.142, (19.433333, -99.133333)),

>>> ('New York-Newark', 'US', 20.104, (40.808611, -74.020386)),

>>> ('São Paulo', 'BR', 19.649, (-23.547778, -46.635833)),

>>> ]

>>> def main():

>>> print(f'{"":15} | {"latitude":>9} | {"longitude":>9}')

>>> for record in metro_areas:

>>> match record:

>>> case [name, _, _, (lat, lon)] if lon <= 0: # Sequence pattern

>>> print(f'{name:15} | {lat:9.4f} | {lon:9.4f}')

Sequence patterns may be written as tuples or lists or any combination of nested tuples and lists, but it makes no difference which syntax you use: in a sequence pattern, square brackets and parentheses mean the same thing.

Note: A sequence pattern can match instances of most actual or virtual subclasses of

collections.abc.Sequence, with the exception ofstr,bytes, andbytearray. A match subject of one of those types is treated as an “atomic” value—like the integer 987 is treated as one value, not a sequence of digits. Treating those three types as sequences could cause bugs due to unintended matches.

Another good example of pattern matching for expression evaluation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

def evaluate(exp: Expression, env: Environment) -> Any:

"Evaluate an expression in an environment."

match exp:

# ... lines omitted

case ['quote', x]:

return x

case ['if', test, consequence, alternative]:

if evaluate(test, env):

return evaluate(consequence, env)

else:

return evaluate(alternative, env)

case ['lambda', [*parms], *body] if body:

return Procedure(parms, body, env)

case ['define', Symbol() as name, value_exp]:

env[name] = evaluate(value_exp, env)

# ... more lines omitted

case _:

raise SyntaxError(lispstr(exp))

Slicing

A common feature of list, tuple, str, and all sequence types in Python is the support of slicing operations.

Why Slices & Ranges exclude the last item?

The convention of excluding the last item works well with zero-based indexing using in Python.

- It’s easy to see the length of the slice. Eg:

a[:3]has 3 elements - It’s easy to compute the length when both start and end indices are passed. Eg.

a[3:10]has 7 elements (end- `start) - It’s intuitive to split a sequence into two. Eg:

a[:3], a[3:]

Slice Objects

This is no secret, but worth repeating just in case: s[a:b:c] can be used to specify a stride or step c, causing the resulting slice to skip items. The stride can also be negative, returning items in reverse. Three examples make this clear:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

>>> s = 'bicycle'

>>> s[::3]

'bye'

>>> s[::-1]

'elcycib'

>>> s[::-2]

'eccb'

The notation a:b:c is only valid within [] when used as the indexing or subscript operator, and it produces a slice object: slice(a, b, c).

1

2

3

4

>>> odd_idx = slice(1,None,2)

>>> nums = range(6)

>>> nums[odd_idx]

>>> [1, 3, 5]

You can also assign values to a slice but it has to be an iterable with atleast 1 item.

1

2

3

4

5

>>> odd_idx = slice(1,None,2)

>>> nums = range(6)

>>> nums[odd_idx] = [2]

>>> nums

>>> [0, 2, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Using + & * with Sequences

Python programmers expect that sequences support + and *. Usually both operands of + must be of the same sequence type, and neither of them is modified, but a new sequence of that same type is created as result of the concatenation.

To concatenate multiple copies of the same sequence, multiply it by an integer. Again, a new sequence is created:

1

2

3

4

5

>>> l = [1, 2, 3]

>>> l * 5

[1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3]

>>> 5 * 'abcd'

'abcdabcdabcdabcdabcd'

Warning: Beware of expressions like

a * nwhenais a sequence containing mutable items, because the result may surprise you. For example, trying to initialize a list of lists asmy_list = [[]] * 3will result in a list with three references to the same inner list, which is probably not what you want.

Augmented Assignment with Sequences

The augmented assignment operators += and *= behave quite differently, depending on the first operand. To simplify the discussion, we will focus on augmented addition first (+=), but the concepts also apply to *= and to other augmented assignment operators.

The special method that makes += work is __iadd__ (for “in-place addition”). However, if __iadd__ is not implemented, Python falls back to calling __add__.

In the case of mutable sequences (e.g., list, bytearray, array.array), a will be changed in place (i.e., the effect will be similar to a.extend(b)).

However in the case of immutable sequences, where a does not implement __iadd__, the expression a += b has the same effect as a = a + b: the expression a + b is evaluated first, producing a new object, which is then bound to a.

list.sort Versus sorted built-in

The list.sort method sorts a list in place—that is, without making a copy. It returns None to remind us that it changes the receiver and does not create a new list.

This is an important Python API convention: functions or methods that change an object in place should return

Noneto make it clear to the caller that the receiver was changed, and no new object was created. Similar behavior can be seen, for example, in therandom.shuffle(s)function, which shuffles the mutable sequencesin place, and returnsNone.

In contrast, the built-in function sorted creates a new list and returns it. It accepts any iterable object as an argument, including immutable sequences and generators.

When a List is not the answer

Arrays

If a list only contains numbers, an array.array is a more efficient replacement. Arrays support all mutable sequence operations (including .pop, .insert, and .extend), as well as additional methods for fast loading and saving, such as .frombytes and .tofile (the serialization/deserialization of arrays are very fast & consume less memory)

A Python array is as lean as a C array since they don’t store references for individual values.

Note: As of Python 3.10, the

arraytype does not have an in-placesortmethod likelist.sort(). If you need to sort an array, use the built-insortedfunction to rebuild the array:

MemoryViews

The built-in memoryview class is a shared-memory sequence type that lets you handle slices of arrays without copying bytes. It was inspired by the NumPy library!

A memoryview is essentially a generalized NumPy array structure in Python itself (without the math). It allows you to share memory between data-structures (things like PIL images, SQLite databases, NumPy arrays, etc.) without first copying. This is very important for large data sets.

A memoryview is a built-in Python object that allows you to access the memory of another object, such as a bytearray, bytes, or any other object that supports the buffer protocol. The buffer protocol provides a way for objects to expose their underlying memory buffers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

>>> from array import array

>>> octets = array('B', range(6))

>>> m1 = memoryview(octets)

>>> m1.tolist()

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

>>> m2 = m1.cast('B', [2, 3])

>>> m2.tolist()

[[0, 1, 2], [3, 4, 5]]

>>> m3 = m1.cast('B', [3, 2])

>>> m3.tolist()

[[0, 1], [2, 3], [4, 5]]

>>> m2[1,1] = 22

>>> m3[1,1] = 33

>>> octets

array('B', [0, 1, 2, 33, 22, 5])

NumPy

For advanced array and matrix operations, NumPy is the reason why Python became mainstream in scientific computing applications. NumPy implements multi-dimensional, homogeneous arrays and matrix types that hold not only numbers but also user-defined records, and provides efficient element-wise operations.

SciPy is a library, written on top of NumPy, offering many scientific computing algorithms from linear algebra, numerical calculus, and statistics. SciPy is fast and reliable because it leverages the widely used C and Fortran codebase from the Netlib Repository.

Most NumPy and SciPy functions are implemented in C or C++, and can leverage all CPU cores because they release Python’s GIL (Global Interpreter Lock).

Deques & Other Queues

The .append and .pop methods make a list usable as a stack or a queue (if you use .append and .pop(0), you get FIFO behavior). But inserting and removing from the head of a list (the 0-index end) is costly because the entire list must be shifted in memory.

The class collections.deque is a thread-safe double-ended queue designed for fast inserting and removing from both ends.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

>>> from collections import deque

>>> dq = deque(range(10), maxlen=10)

>>> dq

deque([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9], maxlen=10)

>>> dq.rotate(3)

>>> dq

deque([7, 8, 9, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], maxlen=10)

>>> dq.rotate(-4)

>>> dq

deque([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 0], maxlen=10)

>>> dq.appendleft(-1)

>>> dq

deque([-1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9], maxlen=10)

>>> dq.extend([11, 22, 33])

>>> dq

deque([3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 22, 33], maxlen=10)

>>> dq.extendleft([10, 20, 30, 40])

>>> dq

deque([40, 30, 20, 10, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8], maxlen=10)

Note that deque implements most of the list methods, and adds a few that are specific to its design, like popleft and rotate. But there is a hidden cost: removing items from the middle of a deque is not as fast. It is really optimized for appending and popping from the ends.

Besides deque, other Python standard library packages implement queues:

queueThis provides the synchronized (i.e., thread-safe) classesSimpleQueue,Queue,LifoQueue, andPriorityQueue. These can be used for safe communication between threads. All exceptSimpleQueuecan be bounded by providing amaxsizeargument greater than 0 to the constructor. However, they don’t discard items to make room asdequedoes. Instead, when the queue is full, the insertion of a new item blocks—i.e., it waits until some other thread makes room by taking an item from the queue, which is useful to throttle the number of live threads.multiprocessingImplements its own unboundedSimpleQueueand boundedQueue, very similar to those in thequeuepackage, but designed for interprocess communication. A specializedmultiprocessing.JoinableQueueis provided for task management.asyncioProvidesQueue,LifoQueue,PriorityQueue, andJoinableQueuewith APIs inspired by the classes in thequeueandmultiprocessingmodules, but adapted for managing tasks in asynchronous programming.heapqIn contrast to the previous three modules,heapqdoes not implement a queue class, but provides functions likeheappushandheappopthat let you use a mutable sequence as a heap queue or priority queue.